Published May 13, 2022

Updated February 28, 2025

H5N1 Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI)

What should I do if I find a sick/dead bird that I suspect may have HPAI?

Unfortunately, the Audubon Society of Rhode Island does not have the capacity to collect dead birds for H5N1 testing. Instead, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (RIDEM) monitors avian mortality within the state.

- FOR ALL SICK OR DEAD BIRDS: The public should report all sick or dead birds to RIDEM at https://dem.ri.gov/report-bird

- FOR SICK BIRDS: RIDEM may not directly respond to every case they receive. If you are concerned about a bird that is still alive, please also contact your local wildlife rehabilitator right away:

- Congress for the Birds; (513) 236-0654 (Providence, RI)

- Sweet Binks Wildlife Rehabilitation; (401) 23-1340 (Foster, RI)

- Wildlife Clinic of Rhode Island; (401) 294-6363 (Saunderstown, RI)

- Find other wildlife rehabbers using Animal Help Now: ahnow.org

The public should not touch sick or dead birds and should keep dogs on leashes and away from carcasses. Always wear proper PPE - at minimum, gloves and a mask– when handling sick or dead birds.

RESOURCES FOR FARMERS: RIDEM has a great resource site on the issue: www.dem.ri.gov/h5n1

What is Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), also commonly referred to as “Bird Flu”?

Avian Influenza is an illness that circulates among wild birds and, until relatively recently, was not a virus known to infect humans.

Waterbirds, such as ducks, geese, shorebirds and gulls are known to be carriers of the virus – spreading it through saliva and feces, while largely remaining asymptomatic themselves. The current outbreak of avian influenza that has been making its way through wild and domestic birds is referred to as H5N1 and receives its name from the surface proteins found on the virus’ surface (H = Hemagglutinin, N = Neuraminidase), which dictate how successful the virus will be at infecting cells and spreading.

There are two types of avian influenza that have been identified: Low Pathogenic Avian Influenza (LPAI), which generally causes no sign of illness or only mild symptoms and High Pathogenic Avian Influenza (HPAI), which causes severe illness in birds and is associated with very high rates of mortality.

The H5N1 virus that is currently circulating in birds is considered an HPAI form of the virus.

Where did HPAI come from?

The first known detection of the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus came from infected geese in a commercial poultry farm in Guandong, China in 1996. By the early 2000s, the virus had spread throughout much of Asia, Africa, Europe and the Middle East. The virus was first detected in the United States in 2014 when it was transmitted from wild birds into domestic poultry, causing an outbreak that lasted until 2016. From the period of 2013 – 2021, multiple global outbreaks of H5N1 resulted in the culling of millions of commercially-produced poultry. In 2020, the global increase in the total number of HPAI outbreaks was greater than the previous 4-years and, in 2021 the virus entered the Americas again for the second time.

Today, the United States, along with over 50 other countries, are grappling with H5N1 outbreaks – mostly impacting domestic and commercial poultry operations, but also increasing in frequency and severity among wild birds. Because of the large number of potential subtypes of the virus, a vaccine is particularly difficult to produce and is cost-prohibitive.

How is HPAI impacting bird populations?

The current H5N1 virus circulating in wild and domestic birds has resulted in the death of hundreds of millions of birds. Over 160 million poultry have been infected with the virus in the United States alone and over 12,000 wild birds have tested positive for the virus (which is a clear underestimate as not all sick/dead birds are being tested). Infected poultry have been detected in 51 U.S states and territories (including Puerto Rico), with over 600 counties reporting nearly 2,000 outbreaks.

In Rhode Island, outbreaks in domestic birds have been confirmed in Washington and Newport counties. As of mid-February 2025, 23 wild birds in Rhode Island have tested positive for H5N1, including gulls (American Herring Gull and Great Black-backed Gull), waterfowl (Surf Scoter, Brant, Mallard, American Black Duck, Canada Goose and Mute Swan), raptors (Turkey Vulture, Red-tailed Hawk and Osprey). In other states, additional species have been impacted such as Great Horned Owl, Bald Eagle, Golden Eagles, shearwaters, murres, kittiwakes, Wild Turkeys and more.

What is the risk of HPAI to humans and our pets?

While the current risk to humans is low, the H5N1 virus is showing a capacity to make a transition from avian to mammalian hosts. Over 900 herds of dairy cattle across 17 states have been infected with the virus, and other mammals, including house cats, are becoming infected.

As of January 2025, 67 human cases of HPAI have been reported (out of over 800 tested individuals) and one death has occurred. At the global scale, a total of 142 people have died from H5N1 since testing began in 2003, including 4 deaths in 2023 and 3 deaths in 2024 (World Health Organization, 2025). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention currently consider the public health risk from H5N1 as low. Despite this, the sustained outbreak that we have seen is concerning due to its increasing prevalence in wild birds and mammals and its rapid spread.

Remaining vigilant about the virus, making sure that you and your pets avoid direct contact with sick or dead wildlife and keeping your cats indoors all greatly reduce your risk of infection with the virus. While there is a great deal of research on the virus, there is still a large amount we do not know.

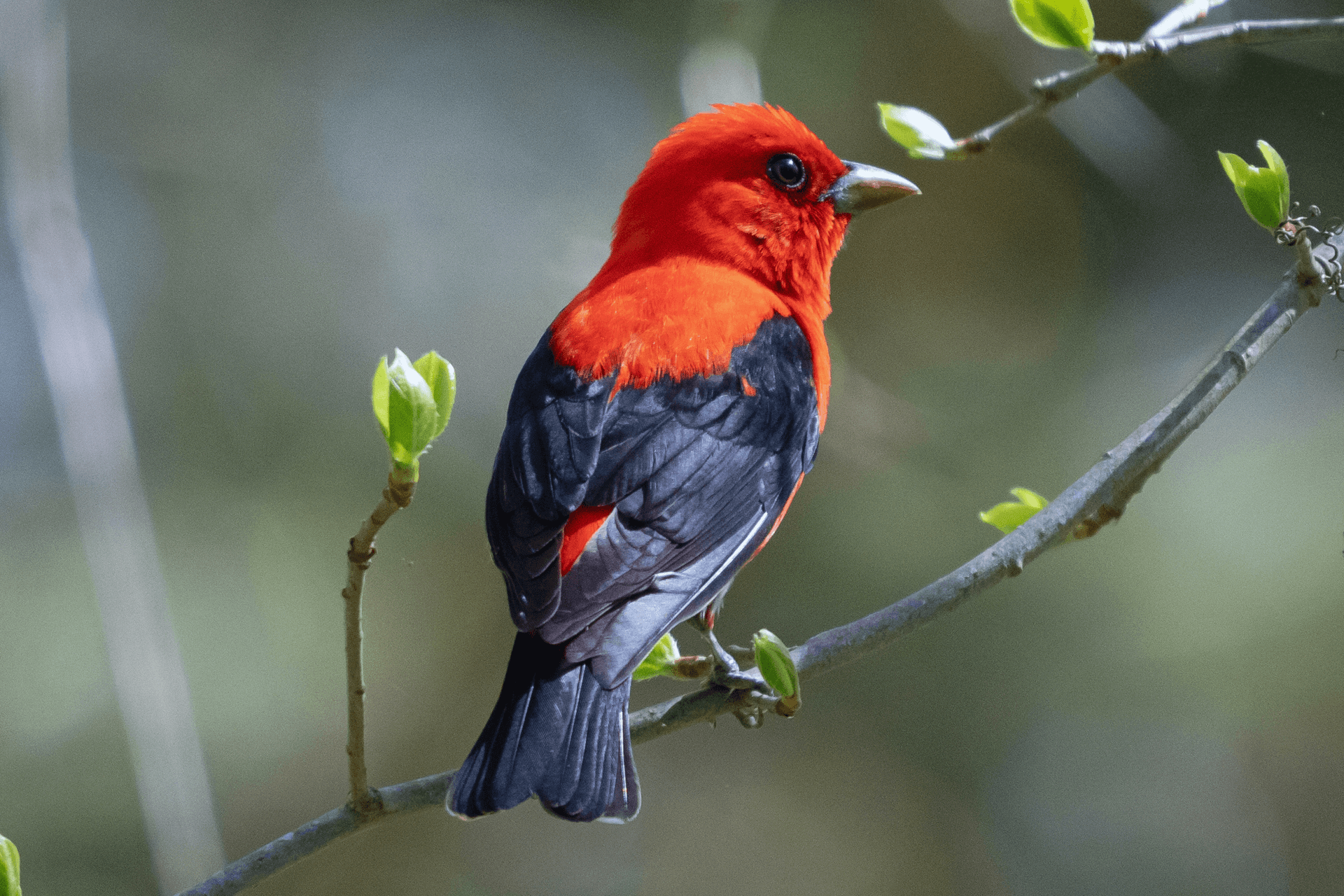

Can I continue feeding birds in my backyard?

HPAI does not appear to infect songbirds as it does poultry, waterbirds and raptors. Therefore, it is still considered safe to feed backyard birds. Ensuring that your bird feeders are cleaned regularly will help prevent the spread of H5N1 (and multiple other illnesses that could be transmitted). If you have a backyard flock of poultry, it is advised that you DO NOT continue to feed wild birds as risk of transmission to your chickens and/or ducks is elevated. It is also recommended that you regularly change your clothing and wash your hands when tending to your backyard flock. If you maintain nest boxes for birds, be sure to wear gloves when cleaning them out and be sure to wash your hands regularly. Read more from Cornell Lab of Ornithology.