Published on June 14, 2023

The State of Our Birds Part II: Migration

By Paige Shapiro

From the unpredictable temperatures to the choruses of spring peepers, one thing is abundantly clear: spring is upon us. These words may excite even the most amateur of birders, as it indicates the long-awaited arrival of the spring migration season.

And although this may be the best time of year for us to break out our binoculars and hit the trails, the reality is that migration is an extremely perilous and strenuous time for birds. For them, the season comes with far more hazardous connotations.

Several years of data analysis have pinpointed western Rhode Island as a hotspot for migratory stopovers, mostly due to its location. Simply put, this area is directly en route to the birds’ final destinations. What this means for Audubon’s Avian Research Initiative is relatively clear-cut: data are needed to properly understand how birds use our properties during migration and what they need to refuel during this period of high risk. How can we help migratory birds succeed as they pass through our state?

As reiterated in Audubon’s State of Our Birds Report: Part I, released in January, North America has lost 30% of its bird population over the past 50 years. This report disclosed data on the distribution, abundance, habitat associations, and long-term population trends of the birds found breeding and overwintering across Audubon wildlife refuges. It was the first release of data from the Audubon Avian Research Initiative––a plan that acknowledges the irrefutable fact of nose-diving bird populations and proposes conservation efforts to help bring them back. The report by Dr. Charles Clarkson, Audubon’s Director of Avian Research, identified nine ‘Responsibility Birds’ that the initiative will focus on to reverse their population decline.

With the recent release of “The State of Our Birds Part II: Migration,” Audubon continues its ongoing trek to learn more about the species that use our properties––this time reaching into the vast world of migration.

Clarkson and a team of volunteers collected data on exactly how birds use Audubon’s properties when they migrate, in comparison to when they breed or overwinter. But as expected, this venture is easier said than done. “The migratory season is highly, highly variable,” explains Clarkson. “How birds utilize the landscape actually changes quite regularly from year to year, even within a single year, and it all has to do with the physiological condition of that bird.”

Migration, as the most energetically demanding period in the life of most bird species, often requires at least a handful of pit stops, and these stopover sites are critical to their journey. Factors like the bird’s initial health, weather patterns, and environmental events instigated by humans (like wildfires, for example) also unpredictably influence when and how a bird uses a stopover site. An American Redstart, whose lengthy flight southward may have historically been punctuated by a stop at a particular parcel of land in North Kingstown, for example, would need to look to uncharted territory if their usual stopover happened to have fallen victim to deforestation. Species are constantly making decisions during migration that affect their success.

“They have to be able to change their behavior,” corroborated Clarkson. “They’d need to find new places to refuel.”

Clarkson notes that while the conservation of large, undisturbed, and well-connected tracts of land is essential to providing breeding and over-wintering habitat, the opposite can be true during migration. Smaller and isolated habitat patches throughout the state can be critical for migrating birds when they need to make unexpected stops due to a lack of resources or severe weather patterns. Audubon protects over 50 properties across the state that contain 20 acres or less. These smaller parcels will be a focus study this fall.

The recent data amassed by Dr. Clarkson identified when migrants tend to show up during migration on Audubon properties, how long they stayed, and the turnover of the species––all things that he believes have to do with resource availability. To simplify: turnover can tell us a great deal about the ability of refuges and protected land to provide the necessary fuel for migrating birds.

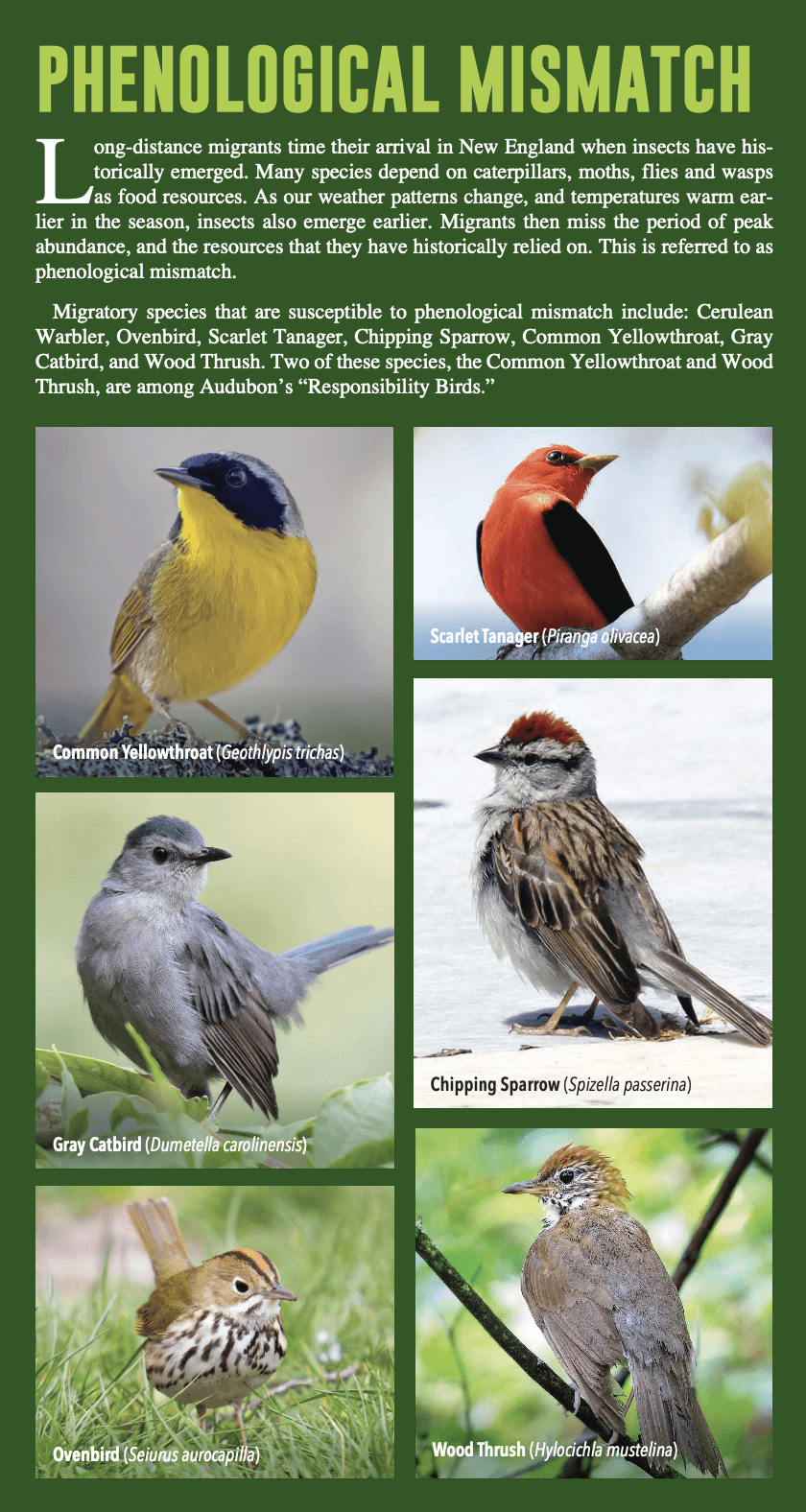

But given the sobering first report, the question that begs an answer still exists: If climate change has indeed induced a premature arrival of the year’s seasons, what does this mean for a migratory bird who cannot adapt as quickly as the changing weather?

Instead, these insects are poikilothermic, their emergence and activity are dictated solely by local temperatures and weather. The harm is evident, then, in spring arriving weeks early. When the Cerulean Warbler arrives every year around the same time in May as they have for thousands of years, they are expecting to be greeted by an abundance of these valuable insects. But as spring temperatures warm earlier and earlier, the bird––a long distance migrant that overwinters in South America––is not “cued into” these local environmental shifts. When they arrive, the warbler has missed the peak abundance of their resources and, in turn, face a higher risk of unsuccessful reproduction.

Paige Shapiro is a reporter for EastBay Media Group and a freelance writer. Reach her at paige.shapiro2@gmail.com.