Published on February 7, 2023

Threats to Rhode Island Tree and Forest Health

By Dr. Scott Ruhren, Senior Director of Conservation

Hiking along the orange trail at Audubon’s Fisherville Brook Wildlife Refuge, you can see dead beech trees with dry bark splitting open. Many beeches at Parker Woodland and Maxwell Mays Wild life Refuges also exhibit the telltale black-streaked leaves of a new disease. Our American beeches are threatened by beech leaf disease and beech bark disease.

Beech leaf disease is becoming more common in southern and western Rhode Island forests. The black streaks are created by nematodes, tiny worms living inside the leaves. Currently the disease is considered untreatable and fatal for infected beeches. Sooty mold fungus of beeches is a bizarre-looking creature linked to beech-blight aphids. The fungus grows in large black masses on the honeydew of aphids. Luckily this does not seem to affect beech health, but in combination with other diseases and the stress of warmer and drier summers, the outcome could be worse. It is becoming difficult to not encounter one of these beech diseases in Rhode Island forests.

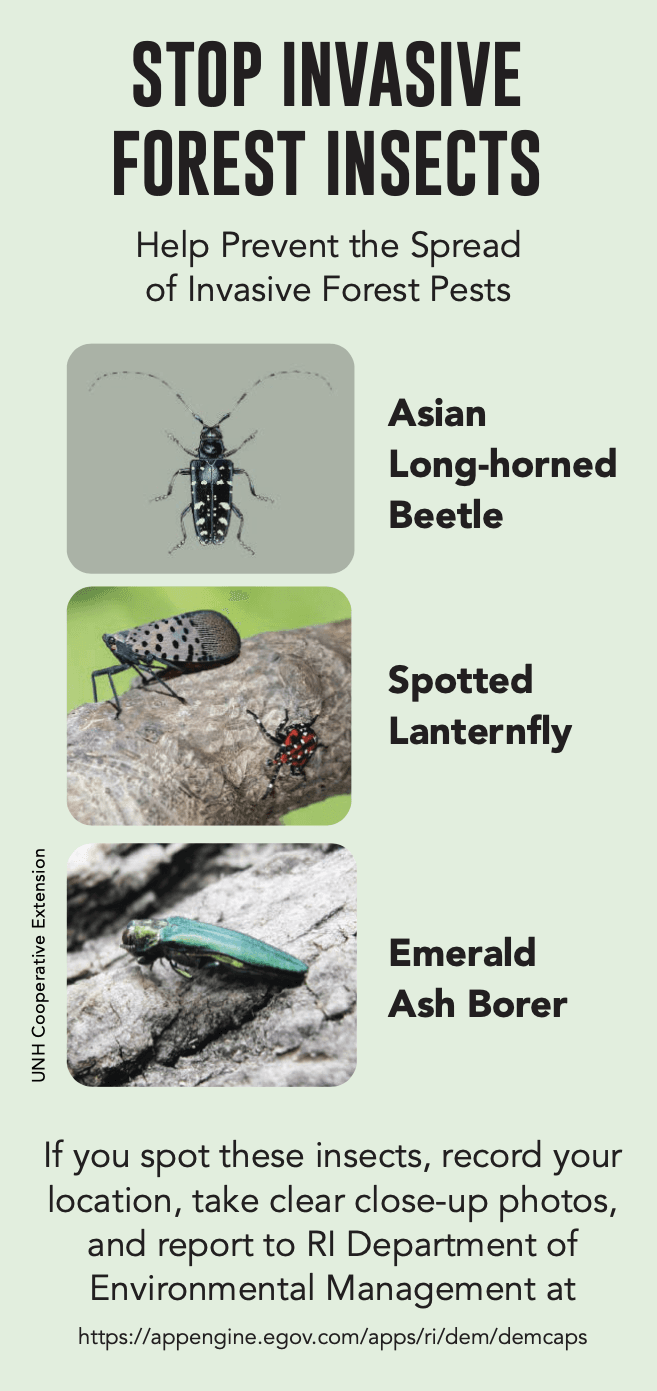

A forest with less beeches means many things. Beech nuts are an important part of the fall diet of Rhode Island birds including Rose-breasted Gros-beaks, Blue Jays, Tufted Titmice, Ruffed Grouse and even Wood Ducks. Gray and red squirrels and eastern chipmunks consume and cache countless beech nuts underground.

This ‘forest story’ is not new. Forests have always had their share of natural biological threats. Parasites and pathogens have a long history with trees. Through time these interactions become more benign, and the impacts may go unnoticed, particularly when trees are healthy and unstressed and the pests are a natural part of the community. This has changed over the past 50 years. Introduced tree pests have altered the forest landscape and led to near extinction of several North American tree species. New forest pests with no local history often render native host trees defenseless. American chestnut is the most infamous example, with this tree’s disappearance leading to change in hardwood forests in eastern North America.

-

Beech Leaf Disease: MA Bureau of Forest Control and Forestry

-

The list of newer forest threats is long. Flowering dogwoods have been stricken with anthracnose, a fungus, and dogwoods have declined in many forests of southern New England.

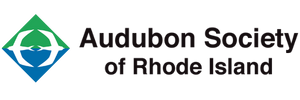

Emerald ash borer, a bright green beetle introduced from Asia, has been found recently in Rhode Island and is predicted to affect native ash species.

Southern pine beetles are making their way north. This is a native species whose range expansion is aided by warmer winters. Several cold winters years ago slowed their march toward New England, but milder winters have been a climate trend in Rhode Island.

Asian long-horned beetles, mostly a threat to native maple trees, is a cur-rent concern. This beetle has been on Audubon’s watch list for a decade. It is realistic to assume that the species will affect Rhode Island maples.

Oaks, a dominant member of local forests, are critical for the survival of many species including insects, birds and deer. Many oaks are faced with leaf wilt fungi, root rot diseases and bacteria that affect the wood. Though one disease in a healthy tree may not cause immediate harm, a combination of pests and environmental stress, like we see today, could be devastating. Spongy moths caused countless oak deaths in Rhode Island.

-

Climate change will likely exacerbate the effects of forest pests. Trees struggle harder to fend off disease, insects and parasites when they are com-promised by lack of water. Some of the die-off of trees from spongy moth is likely linked to drought during record-high summer temperatures.

Audubon monitors forest health and is on the lookout for forest pests that may arrive, such as sudden oak death. We also support the work of State and Federal scientists tracking the insects and diseases. Some simple helpful practices for forest landowners and visitors include not transporting fire-wood and forest products across state lines and reporting sightings of new forest pest insects and diseases.

Resistant cultivars and hybrids of some tree species have allowed for replanting but mostly in residential settings. Treating forests with fungicides or insecticides is not always practical or safe.

What will forests look like for our future generations? Will resistant varieties emerge with protection, habitat management, and monitoring by Audubon? We remain hopeful that forests will remain diverse and resilient. With major roles in climate mitigation, clean air quality, water filtration, and critical habitat for birds and wildlife – the value of forests continues to rise.

-

Dr. Scott Ruhren is the Senior Director of Conservation at the Audubon Society of Rhode Island.