Published March 26, 2024

Timing is Everything, Usually

By Dr. Scott Ruhren, Senior Director of Conservation

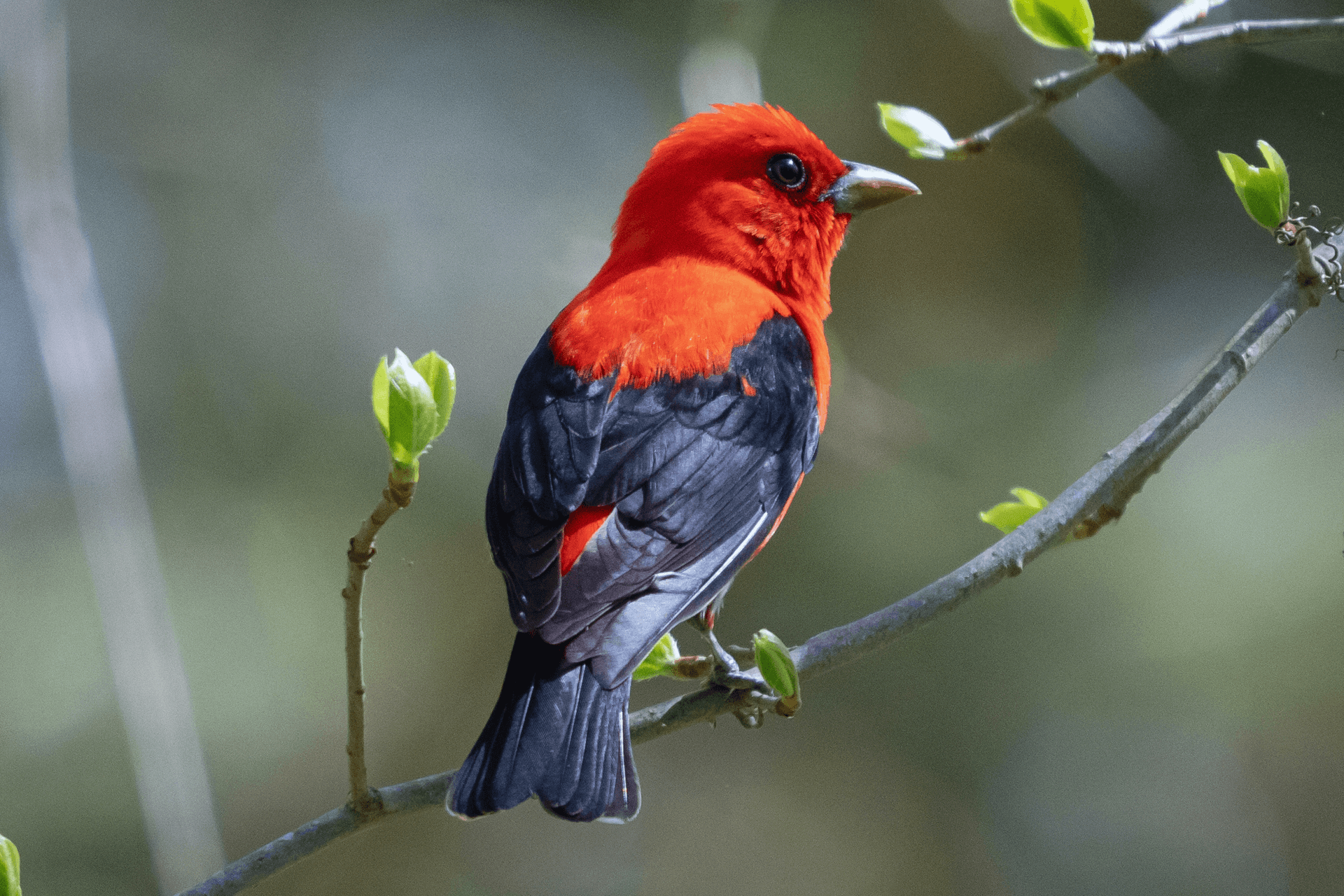

In October, in one evening, warblers headed south strip native viburnums of their nutritious fruits at Audubon’s new Congdon Wood Wildlife Refuge in North Kingstown. In March, as the snow melts, the forest floor warms and spring flowers open, insects will move from flower to flower in search of food.

For forest spring flowers that complete their flowering before the tree canopy closes this “spring window” has decreased by almost seven days since the 1850s when Thoreau was exploring New England. Spring is shorter yet the outcomes vary. Once again bio-logical differences occur. For example, trees are more sensitive—or responsive—to warming than herbaceous species. Invasive plant species are making it worse and several (e.g., honeysuckle shrub species) have a competitive advantage by leafing out faster than their native neighbors.

It has been a troubling 20 years in many cases. Thankfully, biodiversity has its own disaster insurance. Duplicate pieces of the puzzle enhance survival of the species that need those pieces. Pollinators that can use many different flower types could fare better than insects with very restricted diets.

Audubon protects habitat for the species that live on and use our properties and we manage and restore areas to improve conditions and increase “the insurance.” For example, we plant native seed mixes of grasses and wildflowers to feed pollinators and their larvae as well as birds during crucial times in their development. Rather than focusing on single species restoration, we strive to support a diverse mix, based on science with a measure of hope that most will survive.

Most likely, there will be a range of winners and losers in our changing climate. Some species are more flexible and able to respond to changes in timing. Others, more rigid in the life history and needs will likely decline. In the worst cases, local extinctions may occur for species that cannot keep up with their changing world. Adaptive management and knowledge of what species require to survive will help maintain Rhode Island’s biodiversity.