Published 8/20/25

Gould Island: Leave it Wild

A small outpost in Narragansett Bay is worth saving for the birds

By Abbie Lahmers

From the majestic panoramic views on the cliffs of Beavertail State Park on Conanicut Island to the secluded birding opportunities Prudence Island offers, Rhode Island has no shortage of sojourns along the coast for residents and visitors alike to experience the wonders of nature. But some places, emphasizes Audubon Executive Director Jeffrey Hall, “need to stay wild.”

Gould Island is one such place.

The small, uninhabited 53-acre parcel of land, which is part of Jamestown, in Narragansett Bay was requisitioned for the war effort in 1919. Seaplane hangars and barracks were constructed, and portions of land paved over to make way for concrete piers. It was used to store and refurbish torpedoes until the 1950s, before ownership of the southernmost 39 acres was transferred from the U.S. Navy to the State of Rhode Island. Since then, that portion of the island has been deed-restricted as a wildlife sanctuary.

The particular wildness of Gould Island isn’t without remnants of its human-altered past in the form of abandoned military structure ruins and swaths of concrete, and an ungraceful rewilding process that introduced non-native vegetation, but the colonial nesting birds that return year after year are unperturbed by, and even drawn to, some of these apparent blemishes. They seek one feature Gould Island has that can no longer be found in other island habitats scattered around the bay – undisturbed, protected space in which to breed.

As a mounting effort to open Gould Island to the public for passive recreation gains traction among towns surrounding Narragansett Bay, Audubon has made advocating for its preservation a priority. “Audubon manages wildlife refuges that we open to the public for people to get outside and enjoy,” Hall says. “We also have over a hundred properties that are closed to the public. There are places in the state where wildlife should exist without human disturbance so they can live peacefully.”

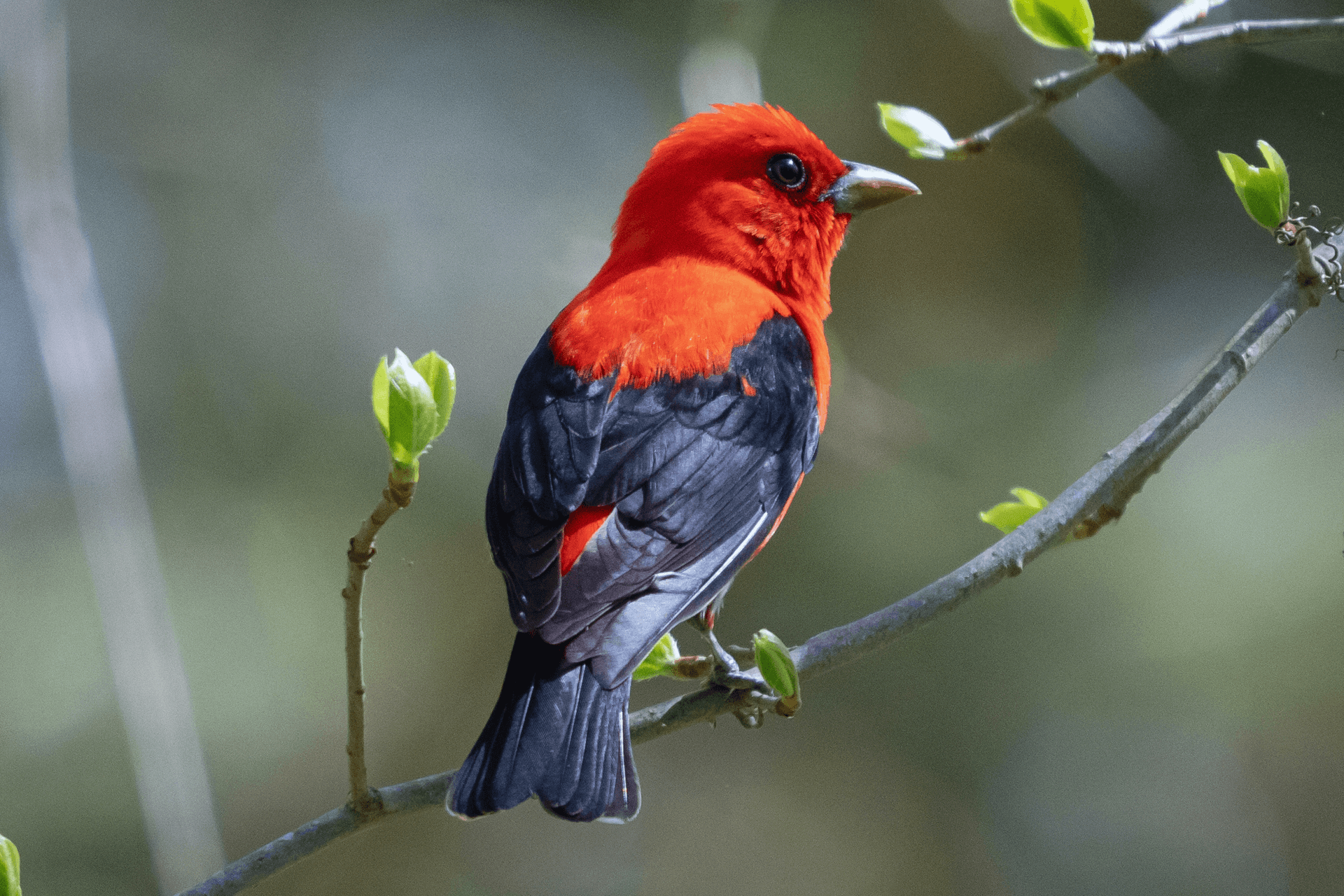

Flocking Together

Since 1964, the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (RIDEM) has been monitoring Gould Island to collect data on the nesting activity of colonial breeding waterbirds – a term that encompasses “birds that nest in large aggregations typically on islands in coastal locations,” explains Audubon Director of Avian Research Charles Clarkson. Four species in particular have persistently returned to breed every year: the Black-crowned Night Heron, American Herring Gull, Great Black-backed Gull, and Double-crested Cormorant. The former three are listed in Rhode Island’s Wildlife Action Plan as species of greatest conservation need. A small breeding population of American Oystercatchers is also supported by the island – another species that makes the State’s list. This designation is in place to ensure these species are prioritized for conservation effort, in this case protected habitat in which to breed.

The steady decline of these species is captured in staggering data documented both regionally and across North America. Clarkson relays that the Black-crowned Night Heron population has seen a 24% drop across the United States from 2012 to 2022, and a 31% decline in Rhode Island in that timeframe. American Oystercatchers are gradually regaining a foothold in southern New England, with one to three breeding pairs present on Gould Island every year since first appearing in 1984, as they recover from a period of being hunted to extirpation, or local extinction, in the area.

Among the most beleaguered species are also some of the least beloved, and deceptively abundant, today – gulls. American Herring Gulls, which are immediately recognizable to anyone who’s spent time along the state’s coastline, have experienced a cumulative decline of 82% across North America from 1966 to 2021, accord- ing to Clarkson, while the Great Black-backed Gull population has dropped by 16% from 2012 to 2022 in Rhode Island, and by around 26% across North America. “The concern over the rapid decline of the Great Black-backed Gull both here and on the global scale has actually prompted conservation organizations such as the International Union for Conservation of Nature to suggest listing the species as vulnerable to extinction,” notes Clarkson.

These statistics are particularly poignant when considering the life cycles of these birds and their relationship with Gould Island – one of the last outposts in Narragansett Bay that supports their continued existence.

“They derive the majority of their food resources, which tends to be a combination of fish and invertebrate prey, from the water around those islands,” Clarkson relays, “and by nesting in these large colonies, they retain certain advantages, such as safety from predators in numbers, and information.” He elaborates that the birds watch one another – they see when an individual sets out to forage, and if its journey proves fruitful, they’ll depart in the same direction for food.

And though Gould is far from pristine in terms of vegetation, with invasive plants encroaching on the overgrown scrub-shrub habitat, the ample cover it offers allows the birds to congregate safely in an area free of coyotes and other predators. Even the concrete sections provide prime habitat for nesting gulls.

For decades, they’ve thrived in this environment without disturbance, but by nesting in tight aggregations, these species are also more vulnerable to threats that can result in outright nest failure. Clarkson indicates habitat loss and degradation, predation events, weather, and, not least of all, human disturbance, as major threats. Unlike more terrestrial-based birds that are distributed on the mainland based on territoriality, Clarkson explains that for colonial nesters, “you're looking at a population of birds that is really concentrated in terms of its use of our state during breeding season. By removing even one site as a potential colony location, you could severely damage the statewide breeding population for these birds. The biological impacts are dramatic.”

A Dangerous Proposal

The Jamestown Town Council has introduced a resolution to open the southernmost 17 acres of Gould Island to passive recreation, specifically overnight camping – a move that has been favored by multiple municipalities along Narragansett Bay, including Newport, North Kingstown, Portsmouth, Narragansett, and Middletown.

“This plan doesn't take into account any sort of wildlife consider- ations,” notes Hall. The Restoration Advisory Board (RAB) has suggested fencing off the forested center of the island for nesting, but the southern edge is the only area the birds have historically used. “That's not how these birds, which have evolved over millions of years alongside certain nesting habitat types, behave,” says Clarkson. “If you take that habitat away, they can't just pick up and move to a new one that they're unfamiliar with and nest successfully.”

Part of the proposal to deacquisition Navy land on Gould Island includes removing any hazardous waste that may be present, a remediation project that would fall under the purview of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The state will have to hire a contractor to determine a management plan, and once that happens, Hall notes the importance of carrying it out with little disturbance: “Any remediation should be taken care of outside of nesting season.”

When that management plan goes out for public comment, Audubon will make a case for why the island should remain closed, informing residents on how crucial it is to preserve such an important ecological space. Since learning of the resolution last fall, Hall explains, “we had to take action and met with Jamestown residents, representatives of the Jamestown Conservation Commission, and Charles [Clarkson] has spoken to a group of concerned individuals.” A letter went out to RAB expressing their opposition, and Audubon has had conversations with RIDEM expressing concern over opening the island. Full-page ads have appeared in The Jamestown Press and Newport This Week, and Hall co-authored an opinion piece with Audubon Board President David Caldwell, Jr. that was published in the Jamestown Press in May. Along with the Jamestown Conservation Commission, Save The Bay is also among community partners rallying against the proposed change.

All these efforts are serving the primary purpose of encouraging further dialogue, and showing the proposal’s supporters, who other- wise may not know, what’s really at stake. Hall explains, “Our immediate goal is to communicate with the people of Jamestown to see if they are willing to pull their resolution. We will then go to all the other communities that have supported opening Gould Island to recreation and try to convince those towns and cities to pull back their resolutions. Audubon also continues to work with RIDEM to discourage this change.”

“We want the State to understand that their own biologists have identified Gould Island as an important nesting area that needs to be conserved,” he continues. “Audubon has the science and research backing us on this issue. Over the last three years, we have put a significant amount of resources into the science behind our advocacy. We are able to make strong, informed arguments on why this island needs permanent protection.

As the RIDEM explores the possibility of removing the wildlife sanctuary deed restriction on Gould Island, it’s difficult to ignore the contradictions in even considering a move that would almost certainly be detrimental to species of colonial breeding waterbirds that, by their own research and data, are in greatest need of conservation. “Removing a deed restriction that establishes a wildlife sanctuary now, during a time when we’re seeing biodiversity loss to such a great degree, is really setting a dangerous precedent,” says Clarkson. “We need to view ourselves as stewards of these wildlife resources and act in their best interest.”

Unintended Consequences

It’s no accident that these gulls, herons, and cormorants return every year. Their persistent pilgrimage to Gould Island is largely due to the absence of other islands providing the same unique advantages, as other options, like Rose Island, have been removed from the equation.

Audubon Board Member Carol Lynn Trocki served on the Rose Island Lighthouse Foundation board a number of years ago. A conservation biologist and advocate for making outdoor spaces accessible, Trocki witnessed firsthand the departure of colonial nesting waterbirds from Rose Island and understands the balancing act between existing in wild spaces and letting others simply be left alone.

She recalls the formation of the Foundation decades ago, which effectively protected the lighthouse and preserved Rose Island from development. In 1999, she says, “the bulk of the island was covered by a conservation easement meant to protect the nesting bird colony and the wildlife refuge, which included restrictions that a significant portion of the island not be publicly accessible during the nesting season from April to August.”

Though the parcel was rescued from becoming home to a marina and condominiums, an increase in human activity over time, all conducted within the regulatory permissions in place on the island, thinned the bird populations once abundant there, despite efforts to keep people away from the designated nesting grounds. “There was a big push to keep expanding the human footprint on the island, and in doing so, I feel like it, very much unintentionally, went past the point of what these sensitive wildlife species were willing to tolerate,” says Trocki.

“I think it’s a very similar story, which is why it proves instructive,” she continues. “My understanding of the proposal for Gould Island is that it is also motivated by a desire to provide recreational access to a coastal area that is otherwise undeveloped.” And though well-meaning, the very logical, human process of drawing lines and creating boundaries in which birds and people can theoretically coexist, is lost in translation for these scrupulous species whose tolerance for us is not what some might wish.

“There are so few places left, in Rhode Island especially, that can be used by these sensitive species of birds that are declining elsewhere. I think it's very irresponsible to consider shifting that balance in favor of human use when it puts wildlife use at risk.”

Strength in Numbers

Audubon’s fight for Gould Island’s protection is only just beginning. On a sweeping scale, notes Clarkson, “Organizations are having a lot of difficulty with regards to funding environmental restoration and protection projects, which means conservation is needed now more than ever.” Hall echoes this sentiment, noting the threat to open space protection and budget cuts as a challenge to these efforts nationwide.

“Getting the message out there, and educating the public, the concerned citizens of Rhode Island, about the plight of these birds is one of the most important things we can do as a conservation organization right now,” Clarkson says.

Though the proposal has gained a lot of traction, its opposition tends to be optimistic that spreading awareness about what’s at stake will shift the tides. Already, a petition to protect the island has garnered over 500 signatures, and Audubon continues to bolster their awareness campaign in the form of letters to the editor in local papers and by showing up to meetings.

One island remaining closed to camping is, arguably, a small sacrifice to ensure many years to come of successful nesting for species vulnerable to a changing landscape, as well as the enrichment their presence brings to all of the spaces to which we already have access. “It's hard for me to imagine living in a coastal state and visiting coastal wetlands and not having these birds present,” says Trocki. “What if we didn't have herons and egrets here in the summertime feeding in our salt marshes? What if we went to the beach and didn’t have terns flying over, fishing offshore, or gulls crying in the area? It wouldn't be the same place.”

The bleak future Trocki describes is thankfully preventable. The case of colonial nesting waterbirds on Gould Island is an opportunity to show how land stewardship can be done well, even if it means walking back an idea that’s appealing at first glance in favor of a future that has many more generations of birds convening in wild and shared spaces, and humans who appreciate them.

Abbie Lahmers is a communications specialist for both the Metcalf Institute at the University of Rhode Island and Roger Williams Park Conservancy, as well as a freelance writer who enjoys hiking, camping, and birding around New England. She can be reached at amlahmers@gmail.com.