By Todd McLeish

At the edge of a 40-acre hayfield behind St. Theresa’s church in Burrillville, long-time Audubon member Cindy Szymanski called out the names of the birds she heard singing – House Wren, Blue-winged Warbler, Eastern Wood Peewee, Common Yellowthroat, Tufted Titmouse, Baltimore Oriole and several more. She spotted additional species darting across the field and soaring overhead.

But identifying the birds was only the first step in Szymanski’s morning of birding. She patiently watched each species she saw for any obvious signs that the birds were breeding. A bird carrying a caterpillar – without swallowing it – was a sign it was bringing food to its nestlings, for instance, or a bird flying away with grass in its beak was an indication it was building a nest.

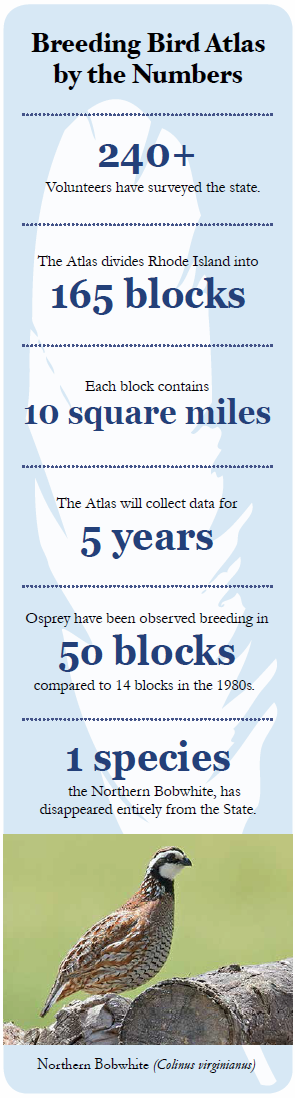

Those observations are crucial data being collected by more than 240 volunteers as part of the Rhode Island Breeding Bird Atlas, a five-year effort to document the breeding status of every species of bird found in the state. The project, now in its fourth year, divides Rhode Island into 165 blocks, each 10 square miles in size. Volunteers scour the various habitats in each block during the breeding season for as many bird species as they can find – day and night – and record any behaviors they observe that indicate whether the species is possibly, probably or confirmed breeding in the block.

Szymanski recorded 77 species in her block by July 1 and had confirmed that 41 were breeding.

Atlas coordinator Dr. Charles Clarkson, a member of Audubon’s board of directors, said that the Breeding Bird Atlas is a way of gathering data to understand the health of bird populations by measuring their distribution, density and use of habitat.

“Birds are bio-indicator species that can tell us a lot about the health of ecosystems. How well bird populations are doing tells us how their habitats are doing,” he said. “The data we collect helps us better direct our conservation efforts. The Atlas is a useful conservation tool used by non-profits like Audubon as well as by state agencies.”

Clarkson describes the process of collecting data as “slow birding,” because it requires volunteers to watch individual birds for extended periods of time while waiting for them to exhibit behaviors indicative of breeding. It requires a great deal of patience, but the payoff in seldom-seen behaviors is high.

In addition to the data being collected by individual volunteers in their assigned blocks, similar information for the atlas is gathered during nocturnal bird surveys seeking to document the breeding behavior of owls, woodcocks and nightjars (species such as the Eastern Whip-poor-will and Common Nighthawks). Biological technicians also conduct “point counts” at designated sites to assess bird abundance. Long-term bird survey data from other sources, like Audubon’s Osprey monitoring program, local bird banding station data, e-Bird and Project Feederwatch, will also be incorporated into the final report, which will take the form of a coffee table book with species accounts and distribution maps. The data will also be available online at the conclusion of the project.

Sponsored by the University of Rhode Island and the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management, the Rhode Island Breeding Bird Atlas is a follow-up to an identical effort conducted in the 1980s, when 68 volunteers documented 164 species breeding in the state. The current atlas has already documented 167 species, but the detailed results will likely be quite different from the previous atlas, due largely to changes in habitat, range expansions, and climate change.

“One phenomenon we’ve seen in the last 30 years is that a lot of early successional, shrubby and grassland habitats have gone through succession and turned into young and mature forests,” Clarkson said. “As this has happened, we’ve all but lost a lot of breeding habitat for species like Bobwhite and Blue-winged Warbler. On the other end of the spectrum, as habitat matured, it’s become available for species requiring older, more mature habitat, like Pileated Woodpeckers and Goshawks. So we’re losing species on one end and gaining on the other.”

The only species that has disappeared entirely from Rhode Island since the first atlas is the Northern Bobwhite, the formerly common member of the grouse family that has become extirpated due largely to the decline of its grassland habitat. Two other grassland species, the Horned Lark and Eastern Meadowlark, have only been documented to breed at several of Rhode Island’s airports, where the mowed, grassy environment mimics the birds’ preferred prairie-like habitat.

The species with the steepest decline in breeding abundance in the state is the Purple Finch, which was recorded in 76 blocks during the first atlas but in only 11 blocks so far in the current atlas.

“It could be that there is an actual decline in the species brought on by habitat loss or competitive exclusion with the related House Finch,” explained Clarkson. “We know they have been in decline in the eastern portion of their range where they overlap with House Finches. But it could also be misidentification by our volunteers.” The two species can be difficult to tell apart.

On the other hand, several species have been documented as breeding in the state that were not found during the previous atlas. These include Kentucky Warbler, Yellow-bellied Sapsucker, Common Raven, Black Vulture and Bald Eagle. It was not unexpected that the raven, vulture and eagle would be added to the state’s list of breeding birds, since they have been seen in increasing numbers in the last decade. Bald Eagles are somewhat common in winter now, and atlas volunteers found them breeding in six blocks.

The most widespread breeding birds in Rhode Island are the American Robin and Gray Catbird. But the Red-bellied Woodpecker has experienced the greatest growth in breeding range since the last atlas. It increased from 4 blocks to 88.

“They weren’t here in big numbers in the first atlas, but now they’re a very common breeding bird, largely due to birds pushing northward due to climate change and the maturing of our forests,” Clarkson said.

Osprey numbers have also increased dramatically from 14 blocks to 50, thanks to the banning of the pesticide DDT in the 1970s, which had caused widespread reproductive failure in the birds in the 1950s and 60s.

The outbreak of gypsy moth caterpillars in the last two years provided an unexpected twist to the atlas results.

“I’ve been intrigued by this cyclical relationship between birds and gypsy moth caterpillars,” Clarkson said. “A few years of bad gypsy moth infestations resulted in a lot of defoliation and the loss of some breeding habitat early in the season, which had an impact on some species. But other species were thriving in those years, especially Indigo Buntings and Black-billed and

Yellow-billed Cuckoos, which eat and feed their young these caterpillars. So those birds experienced a small but obvious boom in Rhode Island.”

Because of the Ocean State’s small size and abundance of volunteers, the Breeding Bird Atlas also includes a winter and migration component, making Rhode Island the first state to conduct a bird atlas outside the breeding season.

“What makes us unique is that it’s a truly year-round atlas,” he said. “We’re not just looking at breeding but also at how birds use habitat in Rhode Island as a migratory stopover place and as an overwintering destination.”

The winter atlas works much like the annual Christmas Bird Count. Volunteers establish a route through the different habitats in their block and identify and count every bird seen. The results indicate the overall distribution of birds that winter in the state while also noting where birds flock together, like ducks along the coastline.

“It helps us visualize where the core hotspots of bird density and distribution are during the winter period,” Clarkson said. “What we’re seeing is that there are far more birds found along edge habitat and neighborhoods than in the interior of forests in mid-winter, which is largely attributed to houses with bird feeders. A lot of birds are drawn to feeders in winter because they represent a stable food source.”

The migration atlas uses trained technicians to walk transects through undisturbed habitat, including at several Audubon refuges, to document bird species and abundance as well as insect abundance as an indication of how long birds may spend in an area to refuel before continuing their migration. That information is coupled with data from weather radar that can show when large numbers of birds depart the region.

“Put these two data sets together and it provides an idea of how each individual transect is being used relative to the others,” Clarkson explained. “If all of the transects are the same habitat, you can understand why one patch of oak forest tends to be more important as a migratory stopover site than another patch. It often has to do with insect density and distance from the coastline.”

While the migration data is still being analyzed, preliminary results suggest that western Rhode Island is especially important to migrating birds heading south in the fall.

“The birds seem to funnel down the state and then move along the coastline,” Clarkson said. “When you compare all of the area captured by Boston radar, we see much higher densities of birds in western Rhode Island than in most other areas.”

As important as the results will be to conservation efforts, the atlas is also playing an important role in engaging people in birdwatching and citizen science.

“I haven’t been very goal-oriented in my previous birding, so it has been good to have guidelines and to have to record data,” said atlas volunteer Cindy Szymanski. “It appeals to my science nerd side. It also feels good to know that I’m contributing something useful and important that will be used in the state for habitat and wildlife management.”

Before the atlas project began in 2015, Szymanski was only familiar with the common backyard birds in her neighborhood. But now she can identify dozens of species by their song alone, and she has developed an appreciation for the diversity of bird life in Rhode Island.

“Perhaps the greatest revelation for me has been the number of warblers whose songs I now know,” she said. “How could those Blue-winged Warblers have been bee-buzzing in the field next door all these years and I never wondered what made that distinctive sound? And I regret not enjoying my favorite bird song, the liquid-sounding Veery, until the last few years.”

Although the atlas is nearing completion, additional volunteers are always welcome.

“We’re always looking for more volunteers,” Clarkson concluded. “We have a lot of flux with volunteers – some move out of the area or aren’t as available as they were in past years – so anyone who can devote some time to the breeding or wintering atlas, even this late in the game, is welcome.”

To volunteer, contact Dr. Charles Clarkson at clarksonce@uri.edu.

Todd McLeish is a life-long birder, freelance science writer and author of several books about wildlife, including “Return of the Sea Otter.”