Published December 1, 2021

State of the Birds

Audubon Begins a New Chapter in Avian Research and Conservation

By Todd McLeish

Audubon Director of Avian Research Charles Clarkson (right) discusses field data with Audubon Council of Advisors member Steve Reinert. Image by Deirdre Robinson.

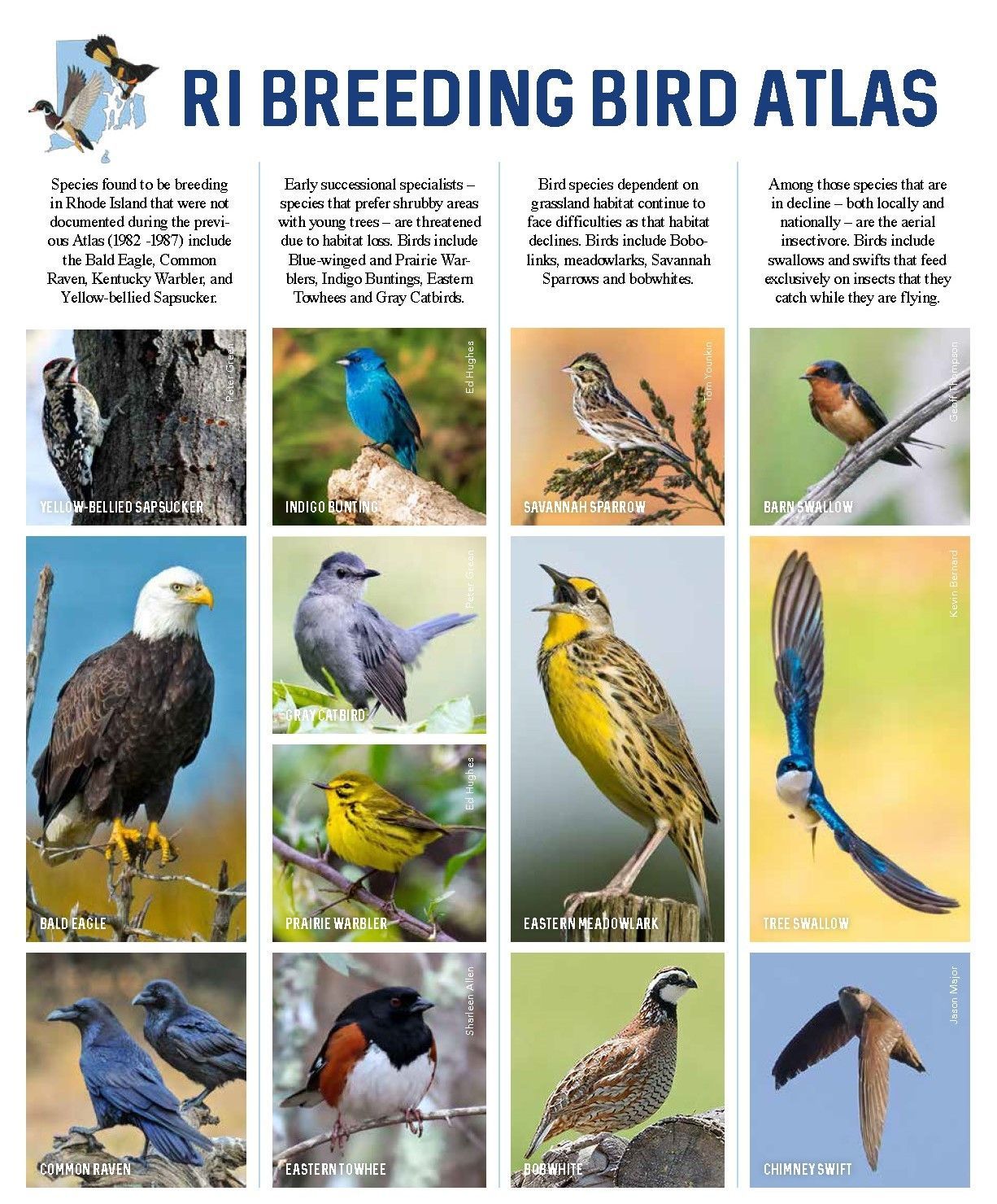

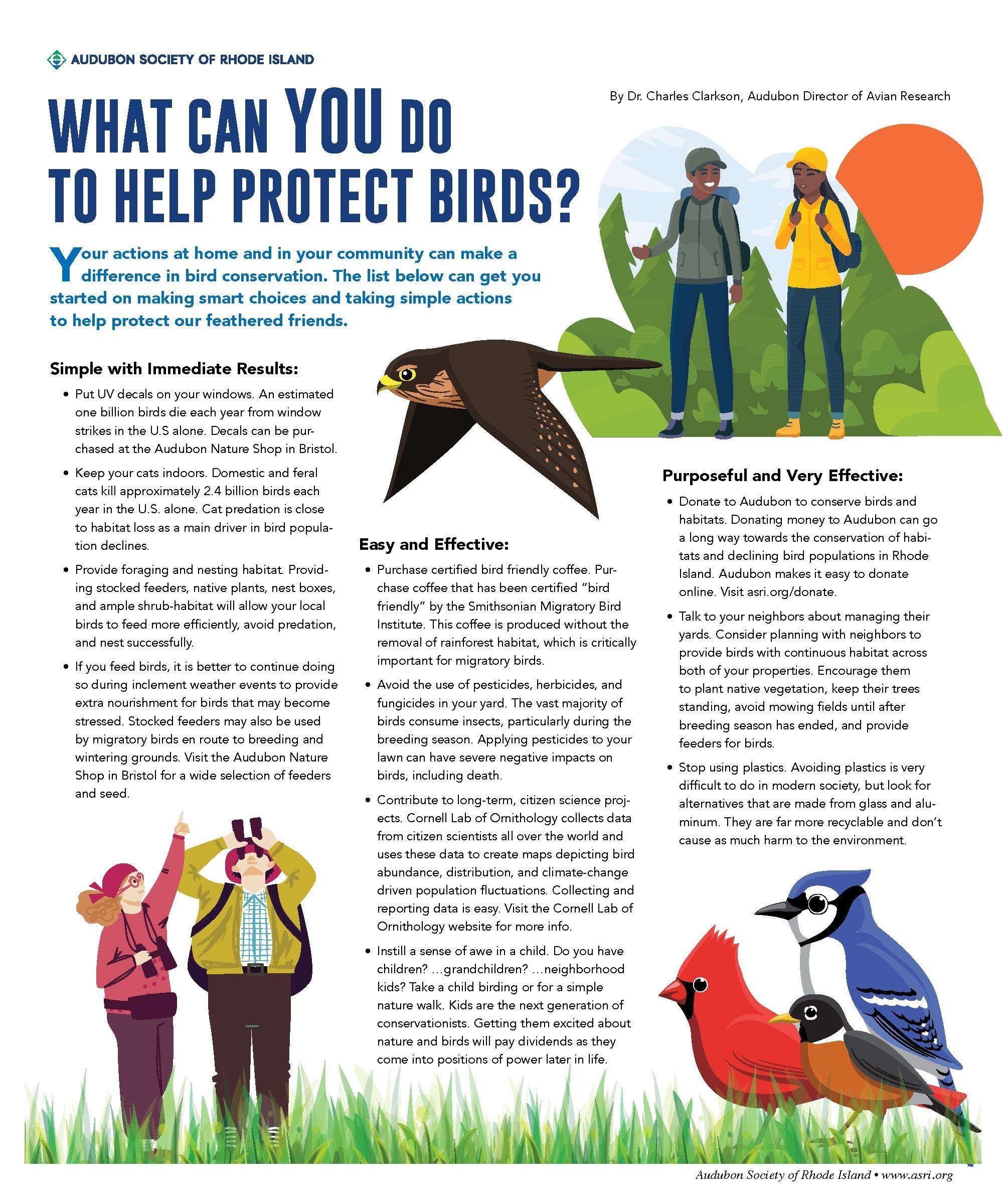

Much has been reported in the news in the last two years about the tremendous decline in bird populations around North America. Scientists say that the continent has about 3 billion fewer breeding birds than it did in 1970, and every ecosystem has been affected. Even species we consider to be common, like the popular Dark-eyed Junco, has had an estimated loss of about 175 million individuals from its population.

These statistics signal a broad crisis occurring throughout the natural world. If birds are in trouble, then so are many other groups of wildlife. And Rhode Island is not immune.

The data on fall migration confirmed that large numbers of birds funnel through Rhode Island every autumn, mostly through the forested regions of the western part of the state. It also concluded that migrants amass along the coast and quickly move on. The winter atlas similarly documented the large populations of birds that are dependent on local habitats during the colder months.

“The good news is that Rhode Island has a wealth of avian diversity still. For a small state with a high human population density, Audubon and other land trusts and conservation groups have done an exceptional job of conserving open space,” said Clarkson. “What’s wonderful about that is that it presents an opportunity to utilize the data from the atlas to effectively manage those populations.

“Now we know where the birds are, the habitats they prefer, roughly how many individuals are breeding, and which species are wintering here,” he added. “Now we can apply what we know in the most effective way possible. We can ask additional questions on some species and focus conservation and land management on other species that are not doing so well.”

“If we experience warming earlier in a given year, the short-distance migrants are capable of detecting that signal and adjusting their arrival dates to coincide with the changes in the weather,” explained Clarkson. “But the long-distance migrants – the neotropical migrants like warblers, vireos and orioles – don’t recognize those changes and so are unable to adjust their arrival times, and they’re the ones that will experience the largest declines due to this phenological mismatch.”

Clarkson said that numerous studies have shown that the aerial insectivores are capable of beginning their migration early in response to the changing climate and arriving in the Northeast to initiate breeding earlier than usual. But that early arrival brings risks as well.

“Just like has happened across most of eastern North America, declining agriculture tends to turn farm fields into mature forest.” said Clarkson. “The question is, do we manage lands for the creation and maintenance of grasslands and early successional habitats, or do we let them success into mature forest? We were a state that was nearly all forested prior to European settlement, and then much of Rhode Island was cleared for agriculture, and now it’s trending back toward forest again. While grassland and early successional species are in decline in Rhode Island, we need to also pay attention to what’s happening with them at a more regional scale.”

Clarkson will be conducting research and providing recommendations for managing habitat on Audubon’s properties – as well as other protected lands around the state - with a focus not just on Rhode Island birds but on the birds that are contributing to regional populations. In his new position at Audubon, he intends to also work with other birding and conservation groups around the Northeast to better understand how bird populations are trending throughout the region and focus efforts on supporting conservation efforts from a wider perspective.

“I also want to borrow an idea from Vermont Audubon that they call ‘responsibility birds,’” Clarkson said. “We need to acknowledge that some species of migrants have 90 percent of their global breeding population in the Northeast, and it’s our responsibility to ensure that conditions never get to the point where we have to be reactive in our conservation. We shouldn’t wait until things get bad before we start to work toward making things better for those species. We need to pay attention to what they need, where their hotspots of abundance are, and make sure the resources they depend on are available in perpetuity.”

The Great Crested Flycatcher is one example of a responsibility bird. It’s a long-distance migrant and the only member of its genus that breeds in the Northeast. Its population is currently stable, and it is considered a low conservation concern. But there are aspects of its biology that make it an ideal candidate for proactive management, including the fact that it nests in tree cavities.