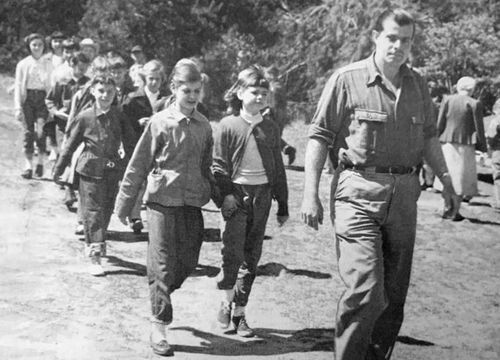

Former Executive Director Roland Clement leading a group of birders at Little Compton, 1958.

Published May 27, 2022

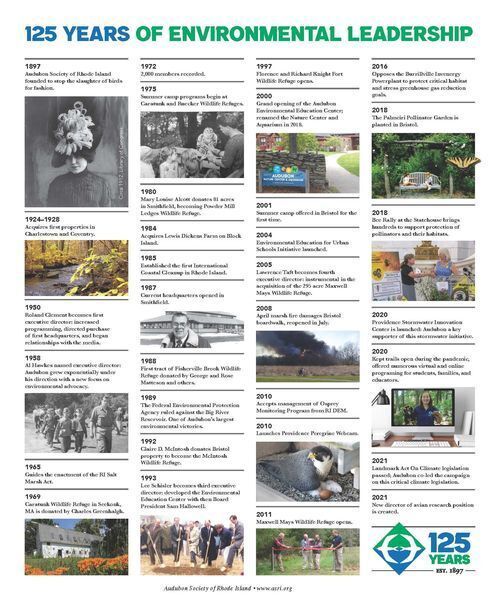

125 Years of Environmental Leadership

Audubon has a long history of rising and meeting the challenges of the day.

By Alan Rosenberg

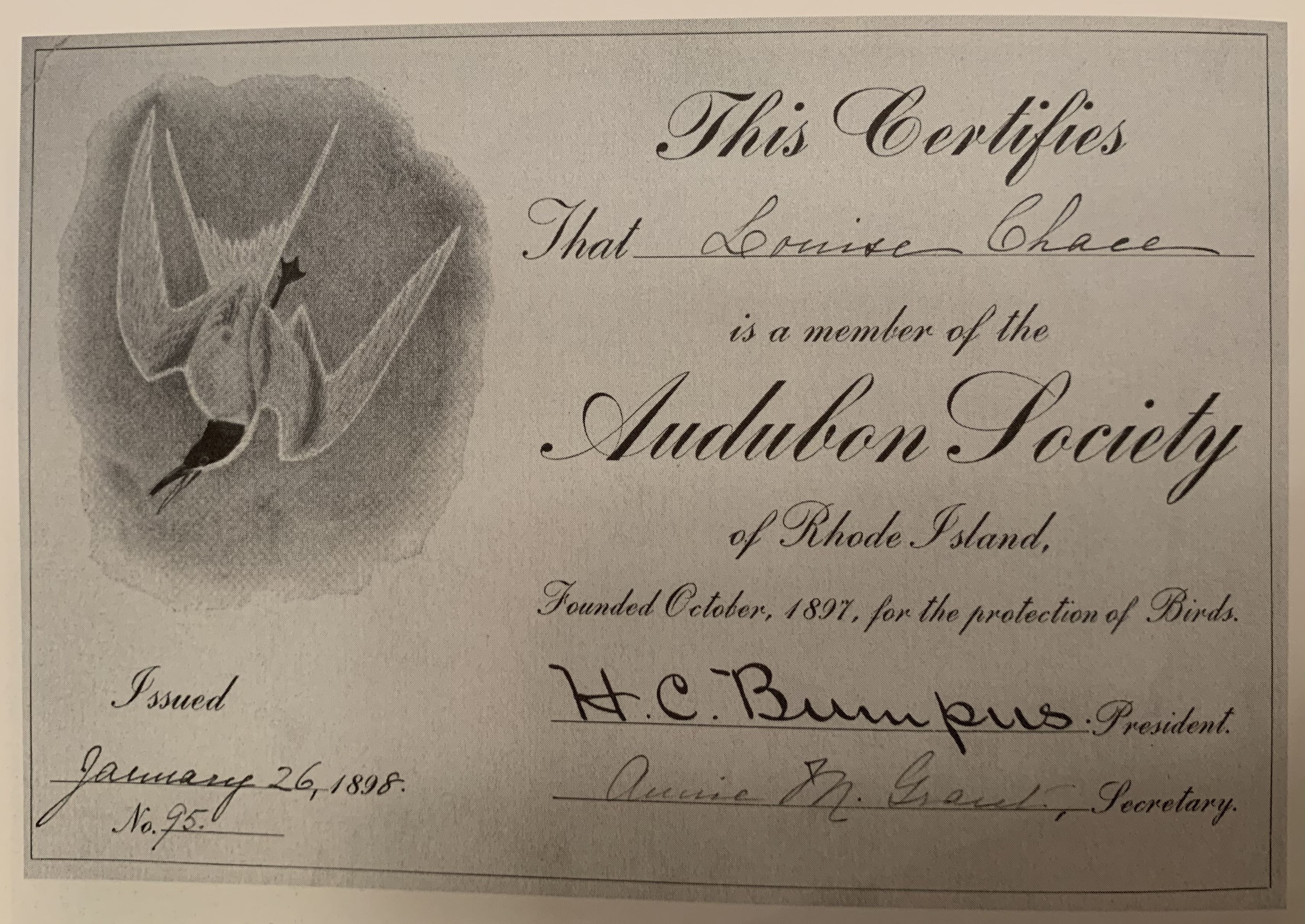

It all began with a fashion craze in women’s hats. The decade was the 1890s – the era known as the Gay Nineties. Part of the gaiety was the display of feathers in the best women’s hats. But to get those feathers, hunters and trappers did something far from happy. They slaughtered birds by the hundreds of thousands: songbirds, shorebirds, birds of prey.

That sparked a movement to save the birds, which originated with the first Audubon Society in New York in 1886. Ten years later, a group of women in Boston founded the Massachusetts Audubon Society and by the following year, several other states joined the cause and formed societies named after John James Audubon, a famed wildlife painter. (Audubon had died decades earlier and was not involved with the organizations — see The Audubon Name story on our blog.)

By 1907, the Society’s membership had swelled to almost 1,300. It was busy with speakers and field trips, and collecting eggs and mounted birds, which – while they wouldn’t be gathered today – were, as Ken Weber notes in his 1997 book about Audubon’s first 100 years, important educational tools in a time before color photos, PowerPoint and the internet.

By the end of World War I, Audubon Societies’ original objectives had largely been met. In 1918, Weber writes, President Woodrow Wil-son signed a migratory-bird treaty with Canada, passed by Congress in 1916, that “virtually put North American plume hunters out of business.” With that success, bird advocates relaxed, and in the upheaval of the Great Depression of the 1930s, many states’ Audubon Societies vanished.

Rhode Island’s didn’t, thanks largely to Alice Hall Walter, a volunteer and forceful personality who served it from 1906 to 1946, raising money, organizing nature walks, recruiting other volunteers, serving on the board and chairing its Education Committee. “I’d call her the grande dame of the Society movement,” the late Roland C. Clement, the Society's first full-time executive director, said in an interview with Weber.

By the 1930s, Audubon had acquired its first two wildlife refuges, Kimball Bird Sanctuary in Charlestown and the first tract of the Parker Woodland Wildlife Refuge in Coventry. Educational efforts continued to expand, and Audubon began publishing its Bulletin, a 16-page magazine issued several times a year. Its first part-time employee, field executive Harold L. Madison, expanded into radio and television broadcasts and a program on nature therapy at Providence’s Butler Hospital. Yet amid all this progress, there was conflict about Aububon’s direction and emphasis. Should Audubon continue to be largely a bird club, or should it become more politically active and issues-oriented?

The discord came to a head in the early 1950s, Weber writes, at a meeting described as a “knock-down, drag-out battle.” A new president, William Dean – leader of a younger, more aggressive faction – was elected, and Audubon’s course was set.

Clement had been hired in 1950 as the society’s first full-time executive director. Trained in wildlife conservation, he began photographing Rhode Island, developing illustrated lectures to tell the story of the state’s ecology, including the pollution of the Blackstone River watershed. He also began a live weekly program on WJAR-TV and sparked a revival of interest that led to an increase in Audubon’s membership. That allowed the hiring, in 1955, of a second full-time employee, to run the Society’s educational programs in elementary schools: Alfred L. Hawkes.

As it fought environmental battles, Audubon didn’t stand alone. Hawkes found allies, both local and national. In the 1960s and early ’70s, “Allens Avenue was a mess in terms of scrap metal and industrial pollution,” Eugenia Marks, former Audubon Senior Director of Policy, recalled in a 2021 interview. Audubon “had very privileged connections on the East Side. That was its history,” she said. So big-name lawyers got involved.

Around the same time, Marks said, “Al was very active with the National Wildlife Federation and the Wildlife Society.” He was key to forming the Environment Council of Rhode Island, ousting the Rhode Island Wildlife Federation – composed of rod and gun clubs – as the state’s affiliate of the national federation. That meant a sea change in how birds and other creatures were perceived: as part of an ecosystem instead of as potential targets for hunters.

Hawkes wanted to develop an Audubon refuge within 20 minutes of every school in Rhode Island, Marks recalled. That goal was eventually achieved through multiple land acquisitions across the state. He also set up a model for the organization with three main emphases: advocacy; education; and land conservation.

As Hawkes wrote in the Audubon Report in 1979: “In the beginning, the concern was for egrets, terns and other birds exploited by the feather trade. Soon, the concern grew to encompass more than birds. Only then did it become apparent that effective laws against the wholesale slaughter of birds or other wildlife are of no value if the habitat they need to survive is destroyed.”

Perhaps Audubon’s biggest battle along those lines was against the proposed Big River Reservoir, a project meant to drown the Big River in West Greenwich and Coventry to build a supplement to the Scituate Reservoir. Audubon fought it from the 1960s until the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency killed the proposed project in 1989, agreeing that Rhode Island’s need for water was not acute enough to justify the destruction of thousands of acres of wetlands and other habitat.

By the late 1970s, Audubon had outgrew its East Side home. When long-time supporter Mary Louise Alcott donated 81 acres in Smithfield to Audubon, the idea quickly grew to build a new headquarters at what would come to be known as the Powder Mill Ledges Wildlife Refuge. It would also house a nature center where people could meet for programs.

After a fundraising drive, Audubon moved into its newly constructed headquarters in 1987. And in 2000, it opened its crown jewel: a $3.5 million Environmental Education Center on the 28-acre Claire D. McIntosh Wildlife Refuge in Bristol. Audubon’s third executive director, Lee Schisler, was the driving force behind this ambitious project with then Board President Sam Hallowell. Along with a 33-foot model of a right whale, an indoor “tide pool” and interactive exhibits, the Bristol site would feature a quarter-mile boardwalk winding through fresh-water and saltwater marshes to a beautiful view of Narragansett Bay. Over the years, it has added more and better marine exhibits, so that Jeffrey Hall, Audubon’s senior director of advancement, now describes it as Rhode Island’s largest aquarium. Befitting that status, in 2018 it was renamed the Audubon Nature Center and Aquarium.

Audubon added another, distinctly modern touch in 2010 when it launched the Peregrine Falcon Webcam, a video camera perched atop Providence’s Industrial Trust “Superman” Building that each spring tracks the nesting, egg-laying, hatching and departure of Peregrine Falcons from the skyscraper, to the delight of 57,000 people who followed their adventures over the internet 275,000 times during the 2021 nesting season.

“I don’t think people [usually] put Providence and raptors in the same sentence,” Hall says. “It shows that nature is adaptive, that these birds are living in the city and you don’t even notice them …”

As the years have gone by, Audubon has acquired more wildlife refuges, including the 2009 bequest of folk artist Maxwell Mays of 295 acres in Coventry, now known as the Maxwell Mays Wildlife Refuge. Mays had bought the land in 1941, and loved to walk it, recalls Lawrence Taft, Audubon executive director since 2005. “He didn’t want a bulldozer to come in and square things off and create a housing development.”

Mays approached other groups as well as Audubon about a potential bequest. But, says Taft, he liked Audubon’s plan to allow the public to enjoy the land as he had for so many decades, and decided the Society was the right steward for it.

Not all Audubon land is open to the public. Hundreds of parcels aren’t – often, small pockets of land that may protect fragile habitat or are not suitable for walking trails or other public use.

Audubon is now more strategic than it once was in deciding what land to acquire, Taft says. “In the past, Audubon would often accept land donations without an understanding of how the property supported birds and wildlife, or any consideration of how it fit into a conservation plan. Now, Audubon looks to see what species it can support.” The Society manages its properties for specific populations of bird and wildlife and may alter its methods if those populations change. Caratunk Wildlife Refuge in Seekonk and Lewis-Dickens Farm on Block Island, for instance, contain large tracts of grass or shrub habitat. These areas are important for Bobolinks, as an example, that nest in fields. But if that species should no longer use the property, Taft says, Audubon might alter the conservation plan to provide for other birds that require critical habitat for survival.

Audubon also looks for ways to expand the boundaries of the properties it owns. “You end up with larger conservation buffers, without the responsibility of managing a new wildlife refuge … often, people don’t know that ownership has even changed. But for us, it’s a reason to celebrate when connected tracts of land remain wild.”

A new chapter in Audubon’s conservation work opened in 2021 as Dr. Charles Clarkson was hired as Audubon’s first director of avian research. His work will guide Audubon’s management efforts and provide a better understanding of the long-term population trends of birds that depend upon Audubon properties. “It’s critical work relating to conservation and climate change,” Taft said, “and Audubon will share these results with other birding organizations across New England.”

A capital campaign that ended in 2019 raised $7.5 million and left Audubon’s endowment in excellent shape, Hall says. But financial challenges aren’t the only ones that nonprofits face. Taft says the organization is committed to making sure that Audubon’s programs and wildlife refuges are accessible to all, including those in urban communities and for people with different backgrounds and walks of life. In hiring new educators, he says, there is now a high preference for applicants who are bilingual, and Audubon is working on translating its website and trail maps into Spanish. Even physical locations are important. It’s no coincidence that the Nature Center in Bristol was built along a bus line and offers an all-accessible trail down to Narragansett Bay to provide visitors of all abilities the same connection to nature. Audubon also has urban birding walks in Providence’s Roger Williams Park, leads summer camps in the city, and brings nature programs to Providence libraries.

“We’ve got to bring our programs and outreach into communities where people live, not always out in the woods,” Taft said. “It’s important to meet and engage people where they are.”

The issues that Audubon faces today are significantly different than those they advocated for in 1897, but the organization still depends on members and supporters who understand the vital importance of a strong and healthy environment. “The largest crisis we have ever faced is here,” said Taft. “Climate change will affect all Rhode Islanders as well as the birds and wildlife Audubon works to protect. Many voices, strong advocacy, and environmental leadership will be critical in the years ahead.”

“Audubon will rise to meet the challenge, as we always have.”

Alan Rosenberg is a former executive editor of The Providence Journal who now helps nonprofits tell their stories. Reach him via email at AlanRosenbergRI@gmail.com.