August 2022

The Audubon Bird Research Email Newsletter provides you with monthly updates outlining the work we are doing as part of the scientific research initiative at the Audubon Society of Rhode Island. You will also receive emails when we are in need of volunteers for projects. Suggestions and questions regarding the newsletter can be sent to Dr. Charles Clarkson, Audubon Director of Avian Research, cclarkson@asri.org.

Sign up to get the Audubon Bird Research Newsletter in your email inbox!

Field Research Update

The type and amount of data collected thus far will allow for detailed analysis of bird-habitat relationships, occupancy, relative abundance and will set the stage for targeted research within the coming years. While the first year of data collection nears completion, we are really just beginning what will be a long-term study of the birds using Audubon refuges.

A summary of the data collected and the products that will be produced:

Things to Come

Once all of the data collected during this pilot year have been analyzed, we will have a better understanding of the bird communities that utilize our refuge complex for some aspect of their annual cycle. Management plans crafted from these data will be designed to promote migrants, residents, overwintering and breeding birds alike.

American Ornithological Society Conference Recap

As is typically the case, the sponsors of the conference included many of the premier conservation groups that have worked diligently to save our birds: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology, The Audubon Society, The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, The U.S. Geological Survey and the American Bird Conservancy. Despite the overwhelming odds facing our birds and the continued lack of action on the part of governments and citizens to take the necessary steps to conserve our biodiversity, I found the atmosphere of the conference to be optimistic, upbeat and hopeful. I caught up with colleagues working around the globe, made new connections and participated in several workshops.

Workshops

A number of workshops preceded the official conference start, each designed to provide training in the use of new technologies or bring individuals using similar data gathering techniques around the world together in one room. Of the workshops offered, I attended two that were devoted to the MOTUS Wildlife Tracking System and one devoted to empowering diversity in the field of Ornithology.

-

MOTUS

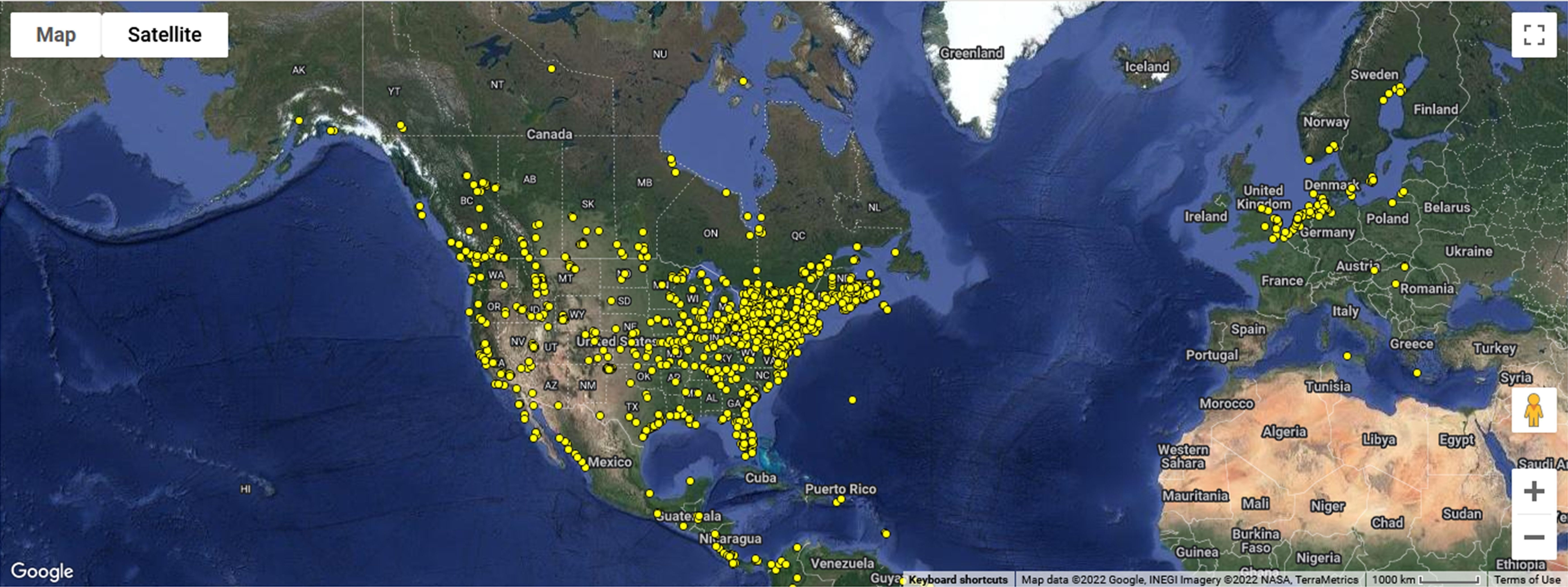

Officially, the MOTUS Wildlife Tracking System is a program of Birds Canada, but through international collaboration, it has grown to what is now arguably the greatest network of animal tracking technology on the planet. The technology utilizes automated radio telemetry to track organisms fitted with radio transmitters. Birds and other animals (such as bats and even butterflies) that have been tagged, are detected by receiving stations installed around the world. Data collected from this tracking technology have allowed us to determine migratory pathways, stopover duration and much more. This information is critical to the identification of resources needed by migratory animals and the creation of effective conservation strategies. Today, 1,474 MOTUS towers and 33,971 tags (across 287 species) have been deployed in 31 countries (MOTUS.org). Researchers using MOTUS have determined the effects of neonicotinoid pesticides on bird movement biology, they have tracked bird migratory response to a changing climate and they have discovered new information about the tactics birds employ when migrating during spring and fall periods.

The MOTUS workshops focused on the creation of strategies to see the technology through to 2030. These strategies include enacting conservation by increasing institutional partnerships (co-production), engaging new audiences through outreach, creating discipline-leading science opportunities, developing an open data framework (to get 80% of data open source by 2027), building community (through regional coordination and empowering collaborations), building capacity through training and data services and innovating technology integration.

It is our sincere hope to bring a MOTUS receiving tower to our Nature Center in Bristol in the near future. This tower will serve to fill gaps in the current network of towers within the northeastern United States and will offer immense educational opportunities here at Audubon. An exhibit within the Nature Center will educate the public on the importance of tracking technologies for conservation as well as display data collected by our very own MOTUS tower. Additional opportunities for in-house and collaborative research will also exist (Figures 1 & 2).

If you are unfamiliar with the MOTUS network or its amazing contributions to our understanding of movement biology, head over to their website (motus.org) to read all about the technology and explore the data collected to date by the project. You can explore migratory tracks taken by a number of species and begin to understand the wealth of knowledge that has been made evident from the new and growing technology.

-

Empowering Diversity

Although ornithologists recognize the significant role of diversity in furthering innovation and conservation, today’s community of scientists does not entirely represent the diversity of humanity. Like many of our world’s disciplines, ornithology was born out of a period in our history when diversity and inclusion were not priorities and, in many instances, were not considered at all by decision makers. The American Ornithological Society (AOS) has been working to rectify this shortcoming. Aside from taking actions to ensure the conference focused on increasing access to underrepresented groups and to foster diversity within the discipline, the AOS hosted a workshop to highlight the barriers to research that students from underrepresented communities face. The workshop provided a pathway for identifying where exclusive tendencies existed and the steps that could be taken to incorporate equity and diversity into decision-making.

During the workshop, specific examples from internship programs within the United States were highlighted and their shortcomings regarding the promotion of diversity and the creation of a safe environment for all were identified. Those of us tasked with hiring technicians, interns and working with volunteers were provided the tools and education necessary to ensure that the door to bird research is opened wide enough so that all may enter, regardless of ethnicity, nation of origin, race, sexual orientation or disability. While I tend to feel as though the field of Ornithology is more accepting of diversity than many other disciplines (37 countries were represented at the conference and 80% of the members of the coordinating committee identified as female), we all have work to do to facilitate the contributions of all who express interest and passion for a subject but may face adversity along the way.

Talks, symposia and roundtable discussions

While the workshops offered during the conference were enlightening and provided essential tools of the trade, the bulk of the conference consisted of individual talks presented by authors of studies conducted the world over (approximately 280 studies were presented). While I attended over 50 presentations, a few struck me as particularly pertinent to our work here at Audubon:

(Click the titles to read more.)

-

Authors: Akresh, M. E., D. I. King, S. L. McInvale, J. L. Larkin and A. W. D’Amato.

The Effects of forest management on the conservation of bird communities in eastern North America: A meta-analysis.

Authors: Akresh, M. E., D. I. King, S. L. McInvale, J. L. Larkin and A. W. D’Amato.

This study investigated species turnover along gradients of silvicultural (forest harvest) intensity. Silvicultural treatments are generally discreet, as a “forest stage” is identified and often maintained through selective logging and habitat management. The study conducted a meta-analysis in which the degree of canopy cover and the amount of cross-sectional stem area (known as Basal Area) were analyzed for forest stands that were less than 15 years post-treatment. The findings of the study suggested that those bird species often associated with shrub/scrub habitats (referred to as early successional habitat) peaked in clear cut areas while species found in mature forest patches tended to drop in abundance rapidly with tree loss. While these results may not seem surprising, a number of species had a quadratic relationship with the two measured forest variables. For shrub/scrub habitats, Gray Catbirds (Dumetella carolinensis) and Indigo Buntings (Passerina cyanea) both preferred intermediate levels of canopy cover and basal area, suggesting that their presence tends to peak and then decline as early successional habitats are newly forming and then mature past a certain stage. A “Goldilocks” scenario, if you will. The same relationship was evident when looking at mature forest stands for species such as Blue-gray Gnatcatcher (Polioptila caerulea), Eastern Wood-Pewee (Contopus virens) and Blue-headed Vireo (Vireo solitarius), suggesting that some tree harvest promotes these species, while too much or too little tends to create a habitat that does not provide for their habitat needs.

Why It Matters: As more habitat is converted to suit human expansion, it is important to know how our conserved forest tracts might be managed if we seek to promote certain species. Studies such as this empower us to make effective conservation strategies for habitat specialists, such as the Blue-headed Vireo, or species with declining trends, such as the Eastern Wood-Pewee.

-

Authors: Augustine, S. H., M. P. Strager and C. T. Rota

Potential population migratory connectivity in Canada Warblers revealed by geolocator tags.

Authors: Augustine, S. H., M. P. Strager and C. T. Rota

This study examined connectivity of migratory routes taken by Canada Warblers (Cardellina canadensis) breeding in WV, which is the only US state with a positive population trend. To determine this, researchers attached 32 geolocator tags to male warblers in 2020 and determined that individuals breeding in WV overwintered in north-central Colombia. Further, the routes taken by birds during the spring and fall migration were offset from one another by an average of 232km (144mi). This suggests a form of loop migration has been adopted by the birds breeding in this region and sheds light on where conservation efforts should be concentrated along migratory corridors.

Why It Matters: The Canada Warbler has declined dramatically throughout most of its range. In Rhode Island, the species has experienced a 59% decline in distribution between 1987 – 2019 and in the states of CT, RI and MA, the species has declined in abundance at a rate of 4.4% per year over a 50-year period. Understanding the full annual cycle of the species, which includes migratory routes taken and connectivity between breeding populations is critical to our ability to reverse this declining trend. Studies such as this, although conducted in a different state, elucidate behavioral and evolutionary trends which can assist with conservation across the entire geographic range of the species.

-

Authors: Anderson, M. A. Valdiviezo, M. Conway, C. Farrell, R. K. Andringa, A. Janik, I. Rusyn and S. Hamer

Widespread exposure of wild bird communities to neonicotinoid pesticides across distinct Texas ecoregions.

Authors: Anderson, M. A. Valdiviezo, M. Conway, C. Farrell, R. K. Andringa, A. Janik, I. Rusyn and S. Hamer

The authors of this study hypothesized that the degree of exposure birds face from neonicotinoid pesticides (neonics) will vary based on genetic similarity, foraging habits, location and season. Within three areas of Texas, 266 blood samples were collected and analyzed for neonics. Almost half of all samples (n = 101) had detectable levels of neonics, with Imidacloprid (the most commonly used neonic) being the most common form detected. Across all seasons, 14 out of 17 avian families had detectable levels of neonics, spanning insect, grain and fruit-eating birds.

Why It Matters: Neonics are pervasive chemicals that can be transported across the landscape due to their properties of poor soil binding and high water-solubility. The potential long-term, chronic exposure risk to birds is great and studies such as this continue to elucidate the threat that these chemicals pose to the health of bird populations in and adjacent to areas of neonic application. This study is particularly pertinent to our work at Audubon because sampled birds came from refuge land, illustrating the capacity of these chemicals to infiltrate protected habitats.

-

Authors: Dossman, B. C., A. D. Rodewald, C. E. Studds and P. P. Marra

Migratory birds with delayed spring departure migrate faster but pay the costs.

Authors: Dossman, B. C., A. D. Rodewald, C. E. Studds and P. P. Marra

The authors of this study utilized the MOTUS Wildlife Tracking System to track the migratory movements of American Redstarts (Setophaga ruticilla) as they migrated from nonbreeding grounds in Jamaica. Individual birds that initiated migration later (only by 10 days), increased migration speeds by 42% to make-up for lost time, but were significantly less likely to survive the migration. This suggests that speed is used to compensate for delays in migration. This compensatory mechanism unfortunately appears to lessen the overall survival of individual birds.

Why It Matters: Birds that find themselves overwintering in degraded habitats are often unable to procure the amount of resources they need to maintain fitness during migration or the subsequent breeding season. This study adds to the knowledge we already possess regarding the carryover effects of the nonbreeding season. It is important to remember that there are birds that overwinter on Audubon refuges and return to breeding destinations north of Rhode Island. Doing what we can to ensure that birds have ample resources to overwinter in good health is one of the goals of the Avian Research Initiative.

-

Authors: Giese, J. C., L. A. Schulte and R. W. Klaver

Grassland bird response to prairie strips in agricultural landscapes.

An example of a grassland strip planted among agricultural fields (photo: Iowa State University)

Authors: Giese, J. C., L. A. Schulte and R. W. Klaver

This presentation highlighted a long-running project in the Midwest United States called STRIPS (Science-based Trials of Rowcrops Integrated with Prairie Strips). The idea is simple: incorporate small strips of native vegetation among rows of agricultural products to provide habitat for birds and pollinators while increasing soil health and water holding capabilities of the landscape. Surveys conducted along rows of native habitat strips documented three times as many grassland bird species using these areas as were found in conventional crop fields. These strips of native vegetation are proving to be significant in their capacity to provide long-term sustainable habitats that promote native biodiversity.

Why It Matters: The STRIPS program is very intriguing as it has established the significant gains to landscape health that can come from devoting merely 10% of total crop area to native vegetation (Figure 3). The idea is simple and the benefits to birds, pollinators, runoff mitigation and nutrient retention are evident. Even small strips of native grassland habitat intermixed with agricultural crops would potentially increase the number of birds associated with these habitats. In Rhode Island, that would translate to more Red-winged Blackbirds (Agelaius phoeniceus), Song Sparrows (Melospiza melodia), Common Yellowthroats (Geothlypis trichas) and others. In addition, trials in the Midwest show that these strips promote four times as many plant species, twice the number of bird species, three times the amount of bird abundance, 40% less runoff, 90% less phosphorus export and 84% less nitrogen export from agricultural zones. This practice, if adopted by RI farmers, could greatly enhance our grassland bird habitat.

-

Authors: Strimas-Mackey M., D. Fink, T. Auer, A. Johnston, O. Robinson, S. Ligocki, W. Hochachka, C. Wood, I. Davies, M. Iliff and L. Seitz

eBird status and trends update: Distributions, abundances and habitat associations for 1000+ species globally.

Authors: Strimas-Mackey M., D. Fink, T. Auer, A. Johnston, O. Robinson, S. Ligocki, W. Hochachka, C. Wood, I. Davies, M. Iliff and L. Seitz

This presentation highlighted new data products that have recently been made available from eBird. Habitat and environmental data from remote sensing are now incorporated into status and trends maps, creating a more refined and accurate result. A complete suite of data products are now available that can be used to visualize bird populations and compare to local datasets to increase our resolution of site-specific nesting biology.

Why It Matters: eBird data has provided some of the best (high resolution) information we currently have at our disposal on bird movements, distributions and abundances. Further refinement of the data is now allowing for the creation of models that account for weather and habitat. These eBird products are capable of informing our work at Audubon because they allow for comparison with the information we gather as part of our baseline dataset, which will also incorporate local habitat variables. This will allow us to determine whether birds nesting in Rhode Island are utilizing habitats the same way that occurs at larger spatial scales. In the event that birds in Rhode Island prefer unique habitats, specific management plans can be catered to the meet these localized breeding criteria.

-

Authors: Morales-Perez, A. L. and O. Monzón-Carmona

Documenting habitat restoration progress through passive acoustic bird monitoring at Hacienda La Esperanza Nature Reserve.

Authors: Morales-Perez, A. L. and O. Monzón-Carmona

The authors of this study placed Acoustic Recording Units (ARUs) in three distinct habitat types (coastal, flood plain and wetlands) and utilized them to determine changes in bird communities as these habitats matured during a period of restoration. ARUs measured change over three habitat restoration phases (1-3 years post restoration) and in three distance categories (50-300m to nearest forest fragment). The authors documented an increase in avian species richness in the oldest sites (2.5 – 3 years post restoration) and those farthest from forest fragments. There was no change in bird communities in those habitat patches close to forest fragments or in those habitats still in the early phases of maturation (<2 years old).

Why It Matters: Although this study occurred in a semi-tropical location, the experimental design and methodology lend themselves well to the work we are doing at Audubon with our ARUs. The ability to use ARUs to measure change in bird communities through space and time makes them extremely useful as conservation tools. Upon completion of baseline data collection across Audubon properties at the end of 2022, our ARUs will be deployed to assess whether the community of breeding and migratory birds changes relative to extent of available habitat or proximity to fragmented habitat patches. This study provided a great deal of insight into the workflow that we will need to adopt to successfully measure these parameters.

Keynote Address: Takeaways

As with all Ornithological conferences, each day begins with a plenary talk given by an esteemed scientist that has contributed greatly to our understanding of bird biology, natural history and evolution. The first of these talks, designed to “kick-off” the conference is often given by someone who has not only contributed to our understanding of birds through years of dedicated research, but is also capable of presenting on a topic that is consistent with the overarching scope of the conference at large. This year, the theme of the AOS conference was “On the wings of recovery: resilience & action”. The keynote speaker was Dr. Herbert Raffaele, a retired Chief of International Conservation for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Dr. Raffaele has authored multiple books, created the Western Hemisphere Migratory Species Initiative, has overseen massive conservation projects throughout the world and has been recognized for his outstanding contributions to conservation with a number of awards.

The title of Dr. Raffaele’s talk was “Saving our World’s Birdlife: A Blueprint for the Future”. The principle focus of the talk was North America’s backward attitudes towards conservation. Dr. Raffaele believes that the key values necessary for the conservation of biodiversity are societal. Instead of focusing on science and the belief that, in order to conserve a resource, we must first understand commonly collected scientific attributes (population size, distribution, habitat requirements and ecology), we should focus on changing culture and the values that societies tend to observe. Dr. Raffaele believes that, in the Western world, there is bias toward biological science rather than social science and to make real change in our wildlife populations, we should focus efforts on stakeholder groups, such as decision makers and teachers as opposed to species groups, such as birds themselves. The identification of societal values that impact the will of individuals and communities to engage in conservation was a primary theme of the talk.

Dr. Raffaele then focused his attention on the nation of India. He believes that this country can teach us a great deal about co-habitation with nature through focusing on culture. The point was made that Hindus (the dominant religion within India) believe that all species have a soul and this very point surpasses all of our primary conservation values. In essence, the Western world believes the greatest amount of conservation good can come from increases in money and space, and a decline in population size. India teaches us that the core belief that an animal has a soul, grants it respect and compassion. And while wildlife roams freely throughout India’s cities and suburbs, the country has devoted very little money or space to conservation and their population continues to grow. Dr. Raffaele went so far to make the claim that, if Hindus had settled the United States, species that were driven to extinction due to overexploitation would still be around.

Where I tend to disagree with Dr. Raffaele’s talk was the decision to compare the United States and its conservation history and current practice with that of India’s. I see the point that, despite having a population that is 4.5x larger than the United States’ and contained in an area that is one-third the size, India is home to 70% of the worlds tiger population and over 50% of the wild Asian Elephant population.

But, this massive population has caused its fair share of problems. India has lost approximately 90% of its biodiversity hotspots and there are currently 94 species of birds threatened with extinction (IUCN). The country as a whole has a been repeatedly said to be undergoing a “biodiversity crisis” and there is a cost associated with such rampant population growth… a very serious cost to the health of our ecosystems, a cost that Dr. Raffaele did not mention.

America is also very different from India and these important differences were not highlighted or discussed, leaving much to be discussed. Hindus did not settle this country, and today only represent 0.7% of its religious makeup (Pew Research). The country is predominantly Christian (70.6%), with more proclaimed Athiests (3.1%) than all Muslims, Buddhists and Hindus combined. How then, do we start from here and get to that “promised land” of conservation? I would have very much liked to hear Dr. Raffaele’s ideas to that end.

Regardless of my criticisms, I agree completely with the talk’s primary message: that our jobs should be to focus on making societal and cultural shifts that recognize the inherent benefit of biodiversity and identify as a part of nature, instead of apart from it. Our technology-heavy hand can be blind to societal issues and instead of focusing on the total number of acres one protects, we should be broadening our attention to the sacrifices that a community makes to live in harmony with nature.

And this is what I truly love about Audubon. While it is one of the largest landholders in the state (and provides an incredibly large amount of high-quality habitat for birds and other wildlife), it is also an organization dedicated to the community. Audubon strives to increase outreach above all else. It offers camps and school programs to bring society into the fold. It gets us a huge step closer to being effective stewards of our beautiful planet because it focuses on both habitat conservation and societal and cultural change.

Parting Thoughts: Travel

Upon walking out the doors on the final day of the conference, I found myself enriched and filled with ideas to bring back with me to my role here at Audubon. I was also filled with an old, familiar sensation that is hard to replicate with anything else we do in life. The sensation of traveling. Visiting far away places (although Puerto Rico is not that far), speaking with locals, eating local foods, all have a very real way of making this world smaller and more manageable. The more of these experiences you have, the wider your understanding of what it means to “Think Globally, Act Locally”. If you don’t travel, you should…even if it is within these great United States. If you haven’t traveled in a while, you should start again. There is a lot to see and do on this wonderful planet.