Published August 2022

Awe-Inspiring: 125 Years of Teaching the Wonders of Nature

By Betsy Sherman Walker

"You are a ladybug whisperer!” Lisa Maloney declares, when a young naturalist and avid wildlife tracker has brought her one of the tiny spotted red beetles he has plucked from a leaf. Maloney, in her position as Audubon Community Education Coordinator, is at the Woonsocket Public Library leading a group of children for an hour of nature discovery on the library grounds. She is there due to a partnership between Audubon and the library and is helping to connect outdoor exploration with the Rhode Island public libraries’ summer theme of “Read Beyond the Beaten Path”. A passionate educator, Maloney is quick to encourage such enthusiasm.

“Woonsocket is a community we have been working with — through after school programs, summer enrichment initiatives, library programs and teacher workshops — for over ten years,” she says. This library program “highlights a partnership we began during Covid, when [the library] wanted to do a series of programs but needed it to be outside. During the school year, this partnership with the library also allows us to reach home-school families in the area.”

The story of Audubon is the story of its educators. In “A Century of Dedication,” Ken Weber’s account of the Audubon Society of Rhode Island’s first one hundred years, the late Rhode Island journalist and nature writer paints a lively portrait of the organization in its infancy. At the time, its founding board of directors — an environmental thinktank of prominent educators, philanthropists, and businessmen —wasted no time in laying out the society’s mission. Promoting and protecting bird life notwithstanding, it is striking that in 1897 this group had the forethought — and the vision — to fortify its bylaws with the line: “and above all, to awaken the interest in children in bird life and thus educate them to humane and gentle sentiments.”

It is a spectacular post-Fourth of July morning in Woonsocket, and the children — about eight total — have come for the first of Maloney’s three visits. The topic today: trees and plants — how they live and grow, interact with their surroundings, and what they can teach us. She hands out magnifying lenses and draws the children in as they walk about, stopping mid-sentence to identify the call, overhead, of a Northern Mockingbird. She moves on to a cluster of hosta and asks, “what might visit a flower?” And answers her own question: “Bees!” She promotes the importance and wonder of the natural world; how we need it — and it needs us. “Protecting nature — that’s our job,” she tells the children, letting them know that this is a responsibility shared by all. Maloney encourages curiosity and is a skilled educator when it comes to engaging the children. She is a frequent visitor at schools, community centers, and libraries like this across the state. In Audubon parlance, Maloney is an imbuer, or one who inspires a passion for nature.

Elizabeth Dickens was hired by Audubon in 1914 to teach bird study on Block Island and she educated generations of children.

—

"That program was a joy to teach. The kids were so interested. They wanted to learn; they asked so many questions. The city kids, if anything, were even more interested, more enthusiastic. The country kids might have known a little more about animals and plants to start, and they usually had more things to bring in.”

– Al Hawkes, Audubon Education Director 1955-58; Executive Director 1985-1993; from Ken Weber’s “A Century of Dedication”

—

The scenario could have been frozen in time, lifted from the early years when the Society’s first educators hit the road with books, pamphlets, essay contests, traveling libraries, traveling exhibits, and Arbor Day activities. With one major exception. Today, the goals of diversity and inclusivity have been securely woven into its mission.

Weber refers to the hiring of Audubon’s first “bird-study” teacher in 1914 as “a shining moment in Audubon’s formative years.” The new hire, Elizabeth Dickens, was a young Block Islander. Dickens’ bird knowledge and passion was transformational. She faithfully — for fifty years — kept a daily birding journal and had famously amassed a collection of mounted birds — 172 of them — which she used as teaching tools. By all accounts she must have been a memorable figure at the front of the class, the consummate schoolmarm in her naturalist’s hat, black stockings and high-top sneakers. Dickens taught “bird-study” until her death in 1963. Weber quoted another Audubon historian (there are many), Joseph Kastner, who in 1986 devoted a chapter in his book, A World of Watchers, to what he called “The Imbuers”— the early generations of Audubon educators committed to “imbuing their passion for birds in children.” And while there were other, equally dynamic teachers who came after, Elizabeth Dickens was — according to Kastner — “the imbuer par excellence.”

From Dickens to Maloney and Senior Director of Education Lauren Parmelee and the current dedicated education staff at Audubon, the thread of that commitment has continued unbroken. Dickens talked about the “joy and value” of teaching birds; Parmelee often refers to instilling students with “the joy of it.” What to teach and how, to whom and why, has kept in step with the evolution of Audubon — which, akin to the rest of the country, experienced a mid-century identity shift. In 1950 the Board hired its first full-time executive director, Roland Clement, a local naturalist with degrees from Brown and Cornell. Clement’s tenure was pivotal. Intrepid in both vision and character, among his many contributions was that he was an avid documentarian of his nature rambles around the state and loved to share his discoveries. He also implemented a schedule of well-organized field trips; thanks to Clement, the Block Island Birding Weekend became a traditional annual outing for serious birders, and to this day remains a signature event.

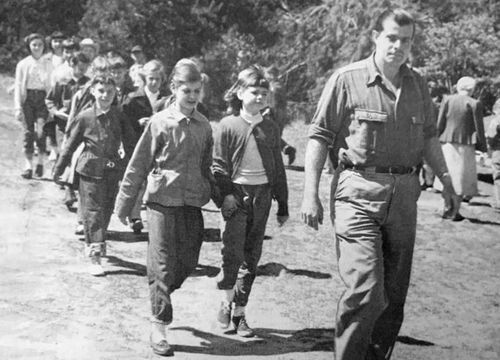

Former Audubon Educator and Executive Director Al Hawkes leading a nature program in Charlestown in 1956

Clement believed that adults had just as much to learn about birds and the environment as children. He would later tell Weber that Audubon “has a tremendous potential that it has not yet begun to realize at all. It has placed most of its emphasis on educating children. Of course, we need to do that, but children do not make economic and political decisions.” The most important investment the Society could make, he added, would be “to design an adult education program to make people understand why we have conservation problems.” Another “shining moment” for Audubon came in 1955, when Clement hired Al Hawkes away from Rhode Island College (RIC) as the Society’s first full-time environmental education teacher. Hawkes, a naturalist who had taught high-school biology before joining the faculty at RIC, shared Clement’s sentiments. Three years later, Hawkes would be handed Clement’s baton as Executive Director.

Entering the sixties, Hawkes stepped — literally and figuratively — into a harsh new world shaped by concerns about DDT and pesticides. The board platform also began to evolve — from an energetic and vocal group of bird and wildlife lovers to environmental activism. In 1969 — a year before Earth Day was launched, Hawkes would present a manifesto of sorts at a National Science Teachers Association conference in Providence: “Conservation, or environmental education,” he told them, “is not a science. It is a moral concept … but it is in no sense of the word science. And it should not be taught as a science.”

Along those lines, Hawkes also proposed a revamp of what college education majors were being taught to use as a curriculum in their classrooms — in short, to focus on more relevant courses that would prepare their students for “the world the student will face when he [sic] leaves school.” He also developed an integrated, K-12 curriculum, beginning with the introduction to plants and animals (similar to what Maloney has put together at the Woonsocket Public Library) and moving into college preparatory courses. When he presented a pared-down version to Rhode Island schools — for fifth and sixth graders — about 30 schools signed on.

From both sides, it got rave reviews. “That program was a joy to teach,” he said.

Hawkes had also overseen the growth of Audubon’s first summer camp program at the Caratunk Wildlife Refuge in Seekonk. By 1996, with 318 children enrolled (in 33 week-long camp sessions), the venue had already outgrown itself and camps had been offered at other wildlife refuges. A new camp location opened at the Nature Center and Aquarium in Bristol in 2001, it now serves approximately 330 campers each summer.

Audubon Executive Director Larry Taft (left) was a camp counselor at the Caratunk Wildlife Refuge in Seekonk (pictured with camp counselor Carol Entin.)

In 1993 the baton passed yet again, from Hawkes to Lee Schisler, an environmental educator from New Jersey and a fellow champion of the holistic approach to environmental education. “I found the three arms of Audubon’s mission — education, advocacy, and land preservation — very attractive,” he said at the time, “and education has always been my first love.” Schisler developed a birds-and-mammals program for seventh and eighth grade science programs (funded by the Rhode Island Foundation); and began to bring programs to elementary school students statewide, as well as into Fall River, MA. Under his guidance, these environmental education programs grew to serve an estimated 15,000 children.

During Schisler’s tenure Audubon developed an even broader education platform and gave it a home. In 1997, as Audubon celebrated its 100th anniversary, it undertook a $3.5 million capital campaign to build the Audubon Environmental Education Center (now the Audubon Nature Center and Aquarium) on the 25-acre Claire D. McIntosh Wildlife Refuge in Bristol. The first of its kind in the state, the Center has become a magnet for birdwatchers, wildlife enthusiasts, summer campers, marine life and Right Whale aficionados, and master gardeners in the expansive pollinator garden.

Today, the Nature Center and Aquarium is the educational heartbeat of Audubon. In the midst of so many moving parts, it is the social and cultural heartbeat as well. It is where the education team keeps calm and carries on, overseeing a large array of environmental education projects and working in a very different social landscape than what 1897 had presented. The unsaid back then is today the oft-repeated: that the children and families of immigrants, or those of African-American descent — residents of inner-city neighborhoods in the early 1900s, with limited access to gardens, yards, fields or forest — were essentially not included in the effort to “awaken” and educate about birds and nature.

Students in an education program on the Maxwell Mays Wildlife Refuge trails with Audubon Educator Tracey Hall.

Hawkes grazed the issue when he described the difference between the city kids and the country kids. But the concept of bringing the latter into Audubon’s orbit did not gain any sense of urgency until the 1990s. Weber quoted Bill Tyler, Audubon Director of Education at the time, as saying that “some of those Fall River kids had never been to a wildlife refuge before. I remember one saying, ‘I’d really like to live here.’”

In 2020 Audubon crafted an updated strategic plan to include a stronger commitment to “the integration of the Audubon Society of Rhode Island into the fabric of the community.” In late May of this year the Board issued a statement, saying “We will continue to challenge ourselves to reach and engage all Rhode Islanders in our mission, particularly communities of color.”

Parmelee’s greatest joy, which is seeing young children discover the wonder of birds and wildlife, is constantly coming up against her greatest challenge, which is securing the funds that will allow Audubon to reach city children, whether through education, transportation, or access. She calls it the funding dance and seems to have mastered all the steps and figured out who she wants to take to the dance floor. In a small state like Rhode Island, she says, there are a “limited number of resources. That’s why we collaborate with like-minded donors and organizations, we need to work together.” Newport’s Martin Luther King Center, for example, fits her model of using donor-funded programming to reach city communities and encourage curiosity and appreciation of nature. “MLK is in perfect sync with our education department’s mission,” she says. “And funding is critical to continue our programs in that community and others.”

Another strategic liaison is with both the Met School in Providence (where Lisa Maloney has created and led several 8-week environmental science series during the school year) and the Greene School, a charter school in West Greenwich that takes students from inner-city high schools and places them in a deep dive into the environmental sciences. Both the Met and Greene schools, Parmelee says, “are top examples of how the Audubon education team serves high school students.”

Although many of her efforts are child-based, surprisingly, Parmelee says the greater challenge can sometimes be engaging the hesitant teacher. Often they need a “spark” to engage with environmental science, to feel comfortable with teaching it, and to be convinced that getting outside is “doable.” It’s not always easy.

At the moment her favorite show and tell is what she refers to as the “Audubon urban education core program” in the Pawtucket third grades —“it is the model of all our city programs.” Maloney has taught and organized this program for years. It serves the approximately 600 children in a given school year spread throughout the ten elementary schools in that city. “I’m particularly proud of it,” Parmelee

To make it all run smoothly she cites the ongoing support of individual donors, the Rhode Island Foundation and the Jane Rockwell Levy Fund, and laments the fact that National Grid, having departed the state, will no longer play a role as a primary funder. Another prominent Audubon location for both after school programs and Summer Camp is the Caratunk Wildlife Refuge in Seekonk, MA which borders Providence — and is hence a bus ride away for the groups of city elementary and middleschool children she works to get outside in nature. As she tries to expand programming in that location, Parmelee mentions a number of donor liaisons, the most recent being a significant gift from the Helen Bracket Trust of $200,000, announced last year to cover transportation, staff education, programming, and teaching materials.

A young camper in Bristol shared his favorite part of Audubon: his teachers.

Another collaborative effort that the Audubon education staff is involved with is the Rhode Island Environmental Education Association (RIEEA). With its army of volunteers and a mission to “raise the voice of environmental education,” Parmelee sees RIEEA as one of the leaders of environmental education in the state. She also had a hand, six years ago, in launching the Schoolyard Habitat Program in Rhode Island in partnership with U.S. Fish and Wildlife, which began on a shoestring $25,000 grant and has morphed from “a little tiny pilot to an enormous collaborative,” involving Audubon, RI Department of Education (RIDE), RI Department of Environmental Management, and URI’s GEMSNet (a science and math program) and other partners. RIDE and Audubon are now collaborating to apply for a multi-million-dollar grant, “to enable schools around the state to have the funding to develop outdoor learning spaces, not only for students but for the communities to enjoy after hours as well.”

Along with wonder and discovery, and the organization’s goals to be more inclusive and accessible, for Parmelee, her staff and collaborators, the final challenge is the reality check of climate change. “It’s all still a matter of teaching,” she says. “You try to weave it into your programs. It’s challenging, to know what to teach about climate and at what grade levels without scaring them.” In place of a term such as rampant CO2, for example, the image of the heat-trapping blanket is used. The important conversation to have, at any age level, is that the “the world is warmer, and how does that affect the earth, nature, habitats, and humans?”

Parmelee is asked about Hawkes’ comment in 1969 about environmental education needing to be taught as a moral concept, not as science. She is quick to acknowledge that he got so much right in his years at Audubon and was a driving force in moving the organization forward. But she also feels times have changed. With the climate crisis upon us, science is now more important than ever. “We still need to engage people in a way that they can relate to and stress the importance of preserving critical habitat, but we also need to present the facts,” she said. “It’s always a balance of being science-based,” – once again speaking from the imbuers’ playbook – “and still trying to teach the joy of nature.”

Betsy Sherman Walker is a Rhode Island native who writes for area nonprofits, news, and lifestyle publications, and who has recently discovered the joy and wonder of birding. Touch base at walkerbets@gmail.com.