Published August 12, 2022

Lasting Legacies: Land Donors Put Their Trust in Audubon

By Betsy Sherman Walker

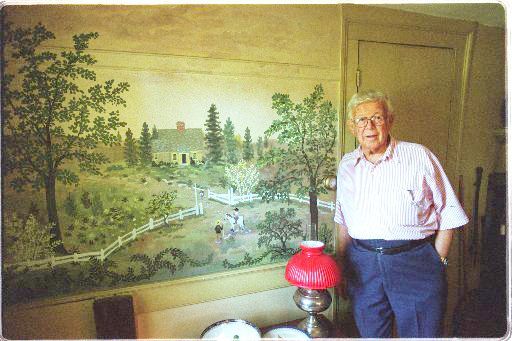

Among the reservoir of stories that reveal her fondness for her late uncle, the artist Maxwell Mays, Allison Barrett has two she likes to share—both having everything to do with his decision, in 2001, to leave his beloved 295-acre Woodlot Farm to Audubon. Mays, the revered Rhode Island painter of bird’s-eye-views of New England life, purchased the Coventry property as a young man in 1941, prior to heading off to serve in World War II.

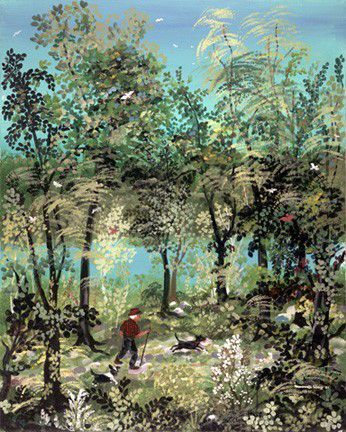

Barrett’s first story is more of an observation, filtered down over the years. She described his childhood on Warwick Neck, which in the1920s and 1930s was a more rural, woodsy area, home to working farms—a far more pastoral retreat than it is today. “He grew up surrounded by property and acres and acres of land,” said Barrett. “It was gorgeous.” And then, with time, she said “he watched it get broken up.” Maybe as if to placate himself, Mays purchased Woodlot Farm from the Carr family, which had owned and farmed it for more than 200 years. During a 2001 interview with Audubon at the time of the transfer, he would explain, “I hated to think of big trucks coming in here and squaring things off.” Barrett tied this to the abundance of trees and foliage, and the stylized leafy details, in her uncle’s work. Even to his scenes of downtown Providence he would add “woods and trees, and vines—very intricate details of vines.”

After returning home from the war, Mays restored the 18th-century farm buildings and made the property his home. Barrett remembers visits to her uncle’s farm as a child, of his love for Woodlot Farm.

Barrett’s second story, again based on reliable hearsay, comes from a day he was entertaining visitors at his lake house overlooking the 11-acre Carr Pond. The sun was out; the surface of the water was speckled with sunlight. One of the guests made a comment about Mays’ being “so wealthy.” To his somewhat surprised reaction, his friend elaborated, telling Mays, “You are incredibly wealthy. Look out on this land—and the jewels in the pond.” It was a moment that resonated and perhaps led the artist to approach Audubon in 2001 with his plan to leave his “incredible wealth” to the organization. Mays lived there (with Barrett and her family nearby) until he died in 2009. His vision for Woodlot Farm officially opened in 2011 as the Maxwell Mays Wildlife Refuge.

Maxwell Mays painting of his property entitled "Woods Walk"

"His biggest dream was to have the land preserved."

– Allison Barrett, Maxwell Mays’ niece

Audubon received its first gift of land, the 29-acre Kimball Sanctuary in Charlestown, in 1924. Today the organization protects nearly 120 properties through fee-title interest and conservation easements, numbering close to 10,000 acres of open space and wildlife habitat. Audubon is the largest private landowner in the state. Gifts over the years have ranged in size from nearly a thousand acres to, in some instances, someone’s cherished half-acre that protected local wildlife.

Each gift has a story, and while each outcome reflects a perspective similar to Mays’, there are multiple factors, Audubon Executive Director Larry Taft explained, that affect the look and feel—and use—of a gift of land. Hidden in plain sight in South Kingstown, for example, is a piece of property with a house donated to Audubon by the late Doug Krauss, a long-time chemistry professor at URI. Krauss was an avid birder and led a bird banding station at the site for many years, beginning in the 1950s. He banded over 30,000 birds for research. When he died in 2000, he left his 84 acres to Audubon providing a residence for URI graduate students who would also carry on his work.

For many the decision — and the process — can be as emotional as it is pragmatic. “One of the first things we do is to find out what a donor envisions,” Taft says. “If it’s a good overlap with our mission, then there’s a discussion.” It’s like a courtship. “When the land is being offered, we have to see if we are on the same page as the donor — if we have a shared vision.”

Mays with a mural in his home

With a similar goal in mind, Shawen Williams’ family story lies at the opposite end of the land-acquisition matrix. Williams, although new to the Audubon board this year, is not a newcomer to the organization. Her father Dudley Williams served as treasurer in the 1960s and 1970s, when the Audubon offices were still located on Benefit Street in Providence. The Williams’ narrative spans close to 125 years—beginning nearly 70 years prior to Maxwell Mays’ 1941 purchase of the Carr Farm, and ending in 1997, a few years before he made his gift. Where Mays’ transfer of his land was relatively seamless (Taft remarked that “it did not take long for us to iron out the details”) the ultimate transfer to Audubon of the Williams’ 240 acres of land on Prudence Island was full of twists and turns — and a cast of characters.

Chipaquisett Wildlife Refuge

Prudence Island, RI

In 1875 Dudley Williams’ great-great grandfather George Washington Williams and his business partner W. E. Barrett acquired approximately 300 acres of Narragansett Bay waterfront on the west side of Prudence Island. It was known as Chipaquisett, a Narragansett term meaning “a place apart.” In postbellum Rhode Island, their vision was to develop it into a summer retreat; “a Victorian escape,” Shawen explained, “from the smelly cities.” The business venture was named Prudence Park. For a while the summer colony thrived.

“Prudence Island,” she said, “became the place to be.” But not for long. The 1890s recession, World War I, and the Great Depression took their toll. The 1938 Hurricane and Hurricane Carol in 1954 had devastating effects. The high-end summer visitors may have been long gone, but families continued to come, joining the small number of year-round residents to spend summers in their Victorian houses overlooking Narragansett Bay. It is where, in the summer of 1948, her parents met. “Prudence Island figures large in our family,” she said.

“Dad was on the Audubon board long before I was old enough to be aware of it,” she said of her family’s involvement. By the time her father joined the board in the 1960s, nothing was left of the Prudence Park his great-grandfather had envisioned. Even the working farms and grazing cows were more or less gone. Her father became its legal caretaker; he paid the taxes and wondered what, if anything, could be done with the 240 remaining acres. He approached Audubon. “It didn’t really constitute a wildlife habitat,” Shawen explained, and the question became moot. It was the establishment in 1987 of the Prudence Conservancy that finally opened the door to a partnership that would ultimately pave the way for turning the “place apart,” with its abundant flora and fauna, into a well-protected Audubon wildlife refuge complete with a conservation easement and deed restrictions (there is no public access without special permission).

Together, Williams and her father initiated the paperwork in the summer of 1996. “There were all sorts of strings attached,” she said, “but it all got done.” In the end, she added, “my father was thrilled.” The Chipaquisett Wildlife Refuge was donated to Audubon in 1997 and years later, Williams said, the family is still being thanked for protecting the land.

Continues below.

Similarly, those looking to connect with nature appreciate the trails at the Mays Wildlife Refuge. “On nice days, people are out there walking and enjoying [it all],” Barrett said. The pandemic lockdown brought people out in droves, she added, from individual hikers to big family groups. “He would have loved seeing so many people walking the woods and trails,” she added. “He would have loved, loved, loved that.”

A walk in the woods with Taft touring the trails around the Powder Mill Ledges Wildlife Refuge is, to a birding rookie, both an education and a revelation. He makes frequent stops, pausing at one point to look skyward at a stand of tall pines, long expired; needles and cones long gone. Still, there are signs of life. Attached up high to the ragged treetops were sturdy-looking bird boxes, move-in ready, for the Saw-whet Owls that return on an annual basis. Further along, Taft points out an array of small nesting boxes — for Eastern Bluebirds — closer to the ground. He talks about species displacement, mentioning House Sparrows and wrens as well as the bluebirds. When Audubon headquarters moved to Smithfield, he said, some wondered why they did not clean up the woods; clear out the dead trees. “We’re not about culling trees and timber. We’re managing [the land] for the birds and wildlife and protecting valuable habitat.”

Land conservation and wildlife protection remain at the heart of Audubon’s mission. Yet there are changes afoot, with the focus becoming more responsive to an evolving population—human as well as avian—and at promoting resilience in the face of climate change. “Thirty or forty years ago there were no land trusts,” Taft said. If a family owned a sizable piece of land they wanted to see preserved, “Audubon back then was the only alternative. We took on a lot as opportunities presented themselves, but there was no focused strategy.” Audubon continues its efforts to grow, but along more strategic guidelines designed to eliminate the growing pains. Climate change has called for protecting coastal areas to serve as storm buffers. Inland, the goal is to preserve more natural spaces and support green infrastructure that can reduce flooding from severe storms — rather than sending the polluted runoff down a storm drain and into the water supply. Audubon also steadily promotes the acquisition of land buffers — smaller yet protective parcels that both help keep the larger properties from directly abutting developed areas, and links them to neighboring tracts of other conservation land.

Last fall Audubon launched its Avian Research Initiative—an all-inclusive project designed to monitor the many bird species that are using Audubon properties. “That will be our cutting edge going forward, Taft explained, “determining how we protect and encourage birds and how our natural landscape fosters resilience.” The overall approach will be to make Audubon’s refuges more interconnected, their care and management more strategic, more efficient, and more of a single, organic whole—with land and wildlife management that is more 21st century than 20th.Continues below.

In a word, holistic. One can’t help but wonder, while considering the historic arc of Audubon’s acquisition and land management practices, if there is a tally sheet. In March, Audubon staff completed a five-year self-audit in seeking accreditation with the National Land Trust Alliance (NLTA) — what Taft called the “gold seal” for a non-profit such as Audubon. The NLTA’s website calls it “a mark of distinction [that] sends a message to landowners and supporters: ‘Invest in us. We are a strong, effective organization you can trust to conserve your land forever.’”

Taft described the exercise as a chance to “look under the hood and focus on the land entrusted to us.” The checklist, he said, presented a valuable exercise in self-assessment. “Are we practicing good stewardship? And how have we achieved this? Are we capable? Is there good governance? Are we sound? Have we protected ourselves—which means our land, birds, and their habitat?” He said he feels confident that all of those questions were answered. “Yes,” he said, “I think we have achieved all of the above.”

While the Executive Director’s work often requires a lens focused on dreams and visions, volunteer Kris Stuart is the office archeologist, seeking answers from cold hard facts. Yin to Taft’s yang, Stuart is a former Resource Conservationist with a variety of conservation districts. She took on the enormous job of pulling together information on each of Audubon’s 120 pieces of property, beginning with the 1924 gift of the Kimball Bird Sanctuary. She dug around through years of Audubon’s records as well as a variety of town halls from as far back as the 1930s. “I like to putter around stuff,” she said.

Betsy Sherman Walker is a Rhode Island native who writes for area non-profits, news, and lifestyle publications. Touch base at walkerbets@gmail.com.