Published August 2022

The Case for Open Space

By Dr. Charles Clarkson, Director of Avian Research

I’ve worked as an ornithologist and more broadly as a conservation biologist for over 20 years. Some of the species that I studied extensively include Gray Catbirds, Prothonotary Warblers, Red-cockaded Woodpeckers, Great Egrets, Snowy Egrets, Tricolored Herons, Blackcrowned Night Herons, Glossy Ibis, and Double-crested Cormorants. I’ve run banding stations where hundreds of individuals of multiple species were tagged each season. I’ve studied birds on the open ocean, in the deepest rainforests and in the most urban places on Earth.

The issues of habitat loss and climate change are not new and they have been dictating our approach to conservation for decades. In almost all cases, successful conservation occurs through habitat preservation and restoration. Nest boxes installed along the James River in Virginia provided an essential resource for Prothonotary Warblers and, to date, over 600 nest boxes have recruited more than 26,000 warblers to the Virginia breeding population. To conserve Red-cockaded Woodpeckers, we focused on maintaining the pine-wiregrass savannah habitat of the southeast by removing deciduous trees and performing controlled burns across the landscape. The nonbreeding season was spent managing these habitats and drilling nesting and roosting cavities for the endangered woodpecker population. Along the coast of Virginia, where 42 percent of tidal wetlands will be lost by 2100 due to climate change induced sea level rise, habitat restoration projects aim to ensure that predator-free nesting sites for colonial waterbirds remain (the waterbird populations in Virginia have been in decline since the 1970s and the loss of suitable breeding habitat has been identified as a major contributing factor).

Gray Catbird (Dumetella carolinensis) by Peter Green

Despite the good work that is taking place across our globe to restore habitats and the bird populations that rely on them, it is easy to get discouraged by the growing urgency of the situation.

Our global environmental report card does not show much to be proud of. Despite the Paris Climate Agreement’s goal of limiting global temperatures to 1.5o C above pre-industrial levels, we are currently on track to experience warming of 2.7o C. This degree of warming will have devastating impacts, increasing poverty levels, habitat loss and sea level rise (source: NRDC). The human population is still growing, with projections that we will reach 9.7 billion people by 2050 and 11.7 billion by 2100 (source: United Nations). Obviously, this growth means that the per capita availability of resources will continue to shrink, affecting the most impoverished first and most intensely and leaving little natural habitat for the wildlife populations that remain (wildlife populations across the globe have declined by 68% since 1970 (source: World Wildlife Fund).

The more I do this job, the more it rings true that birds are living in a man-made world and the amount of “wild” is disappearing before our eyes.

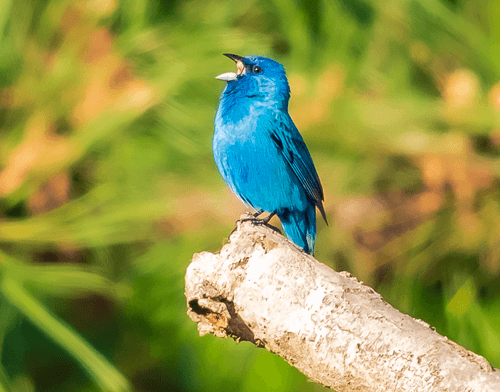

When these feelings of discouragement or hopelessness seep in, I head for the woods. A few hours spent walking the trails of one of our refuges has a way of refilling my well. I spend quality time watching a Scarlet Tanager preen in the sun, I watch an Indigo Bunting singing incessantly from a branch or I locate a slinking Yellow-billed Cuckoo and become a one-man audience for a few minutes of cryptic theater.

Indigo Bunting (Passerina cyanea) by Ed Hughes

When I spend time on our refuges, I am reminded of an undeniable truth that you don’t need science to substantiate: conserving open space is a massive benefit for birds. Species found rarely on the outside of a refuge are often common and even abundant within its boundaries. Wildlife Refuges serve as oases and even the smallest plot of land can provide essential resources for a bird. My role at Audubon is not to provide the data to show that birds use our refuges (although it will), but rather to better understand what species are present throughout the year and what MORE we can do to protect them.

If we stopped emitting greenhouse gases and ended our rampant consumption of natural resources tomorrow, it would still take decades for the effects of these long-standing drivers of decline to release their grip on our wildlife populations. There is hope that, at some point in our future, we will not have to focus so much of our attention on conservation and restoration. In this utopian future, birds and other wildlife will flourish once again and we will finally coexist with nature instead of stripping it from our daily lives.

Until that day arrives, our refuges provide resilient strongholds where birds can ride out the effects of climate change, habitat loss, house cats and other threats. And, the more land we protect, the more breathing room we provide for beleaguered wildlife populations. So, while science is a strict discipline that can provide data and a wealth of data-driven products useful for conservation, sometimes the simple solutions are indeed the most impactful.

The war for our future rages on, and it remains to be seen whether biodiversity will be a winner or loser in the long run. But, be assured, the protection of even the smallest amount of land from development and industry is a win in the battle to rewild our planet.