Lessons learned

States and local jurisdictions plan for and mitigate future risks based on their unique needs and circumstances. Nevertheless, the actions featured in the policy briefs provide a variety of lessons for other jurisdictions to consider as they develop their own mitigation policies.

Invest in planning—and understand the risks

Some of the most effective mitigation policies first took shape following efforts to understand the root of a flooding problem. Officials in Washington state used an Environmental Protection Agency grant to study the state’s flooding problem before presenting a solution to the Legislature. Minnesota assessed flood impacts to transportation assets, such as roadways and bridges, and identified projects based on the costliest and most frequent closures of those assets due to flooding. In both cases, officials maximized the effectiveness of limited funding by being deliberate in examining vulnerability to floods and the greatest sources of possible disruption.

In South Holland, Illinois, a resident committee assessed options for combating flooding, leading to a proposal that eventually became the city’s rebate program—which has since led to more than 1,000 households strengthening their properties against flood risk. On a larger scale, Iowa dedicated an agency to studying flood models and related patterns.

Use regulations and cost-shares as cost-effective options

Several states and localities are driving down the cost of flood mitigation by using regulations to guide development away from high-risk areas as well as establishing policies that maximize the value of relatively small upfront government investments.

Fort Collins’ flood plain regulations, Norfolk’s zoning ordinance, and Brevard’s no-adverse-impact certifications are helping to ensure that housing, infrastructure, and other assets are located away from vulnerable areas, thus minimizing damage when floods occur. Indiana’s revolving loan fund maximizes the impact of a relatively small investment by making low-interest loans for mitigation projects to jurisdictions that then repay them so that others can take out similar loans.

Other policies leverage cost-sharing, in which jurisdictions combine their own resources with funding from individual homeowners and other levels of government to cover the expense of flood mitigation. Wisconsin’s buyout program, for instance, provides up to half the cost for local mitigation projects, and municipalities make up the remainder.

Tap into nature-based solutions

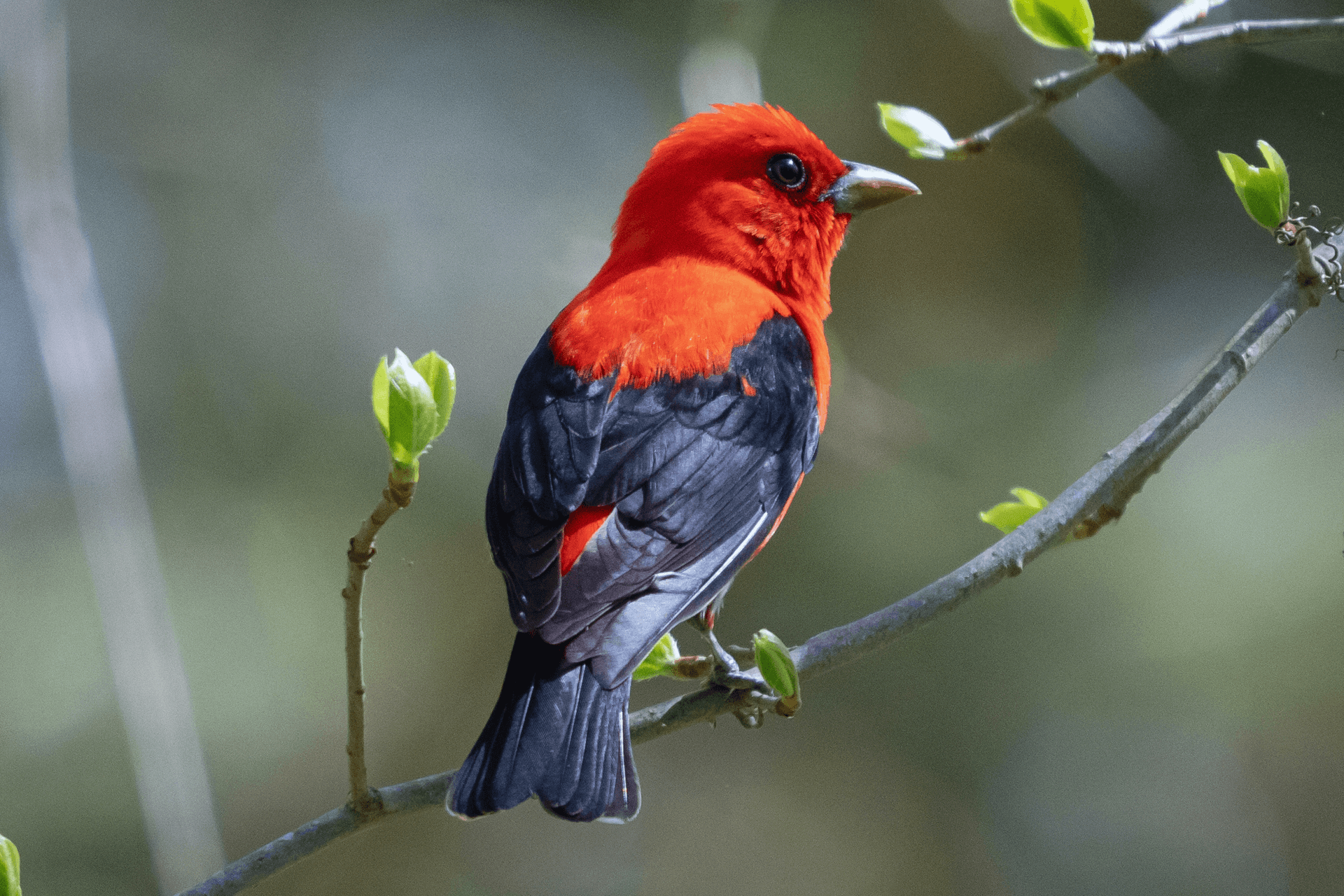

When designing policies to improve disaster resilience, some states are leveraging the benefits of nature-based solutions, such as creating open spaces and restoring wetlands, which serve as buffers between oncoming storms and otherwise vulnerable communities.

Maryland’s living-shorelines regulations prioritize the use of native plants and other natural elements that stabilize coastlines, reduce erosion, and mitigate flood damage, as opposed to structures like levees and seawalls. Buyout programs such as Wisconsin’s can replace hard surfaces such as concrete with green spaces such as parks and wetlands, which better absorb rainwater and bring additional benefits to communities, including providing places for recreation.

Officials in these states and others are nurturing more sustainable communities by weighing the impacts of development decisions on natural flood plains. And some places are moving to policies that reverse previous actions that manipulated bodies of water, such as Washington state’s history of straightening its rivers and Milwaukee’s lining of streams with concrete. Some communities have come to realize that these disruptions of natural waterway functions actually increased their flood risk and have since turned to nature-based solutions.

Communicate the benefits and engage stakeholders

Many programs’ effectiveness depends on whether communities understand how to take advantage of them, and how well municipalities collect feedback and improve the programs. Arkansas’s tax credit incentive has proved immensely popular in communities where awareness has spread through word-of-mouth, but other communities in the state have not seen the same level of interest. And while a significant portion of residents have used South Holland’s rebate incentive, program managers believe more would take advantage of it if they better understood the benefits.

In Iowa, officials have used the state’s network of Water Management Authorities to bring stakeholders into the conversation about curbing floods and to ensure that their concerns about the state’s mitigation program are addressed.

Make policy changes part of recovery efforts

As communities try to recover after flooding, some legislatures have responded by passing forward-thinking laws aimed at lessening the impacts of future floods. For example, after Tropical Storm Irene, lawmakers in Vermont created the ERAF program, which rewards localities that take measures to reduce their future risk.

Likewise, in Norfolk, the persistent problem of sea level rise motivated officials to improve the city’s zoning ordinance, buoyed by polls showing that 70 percent of city residents were concerned about flooding. As communities encounter more frequent and widespread damage from storms or rising seas, they can harness residents’ awareness and concern to initiate positive change.

Conclusion

Pew’s research highlights state and local policies and regulations that have been important catalysts for flood mitigation. As green spaces expand, wetlands recover, natural shorelines are created, infrastructure becomes more resilient, and homes are removed from or not built in vulnerable areas, communities are reducing the impact of future floods.

Although there is no one-size-fits-all solution to the threat posed by more frequent and severe flooding, the 13 policy briefs provide a variety of models for officials to consider when trying to make their own communities more resilient.