December 11, 2018

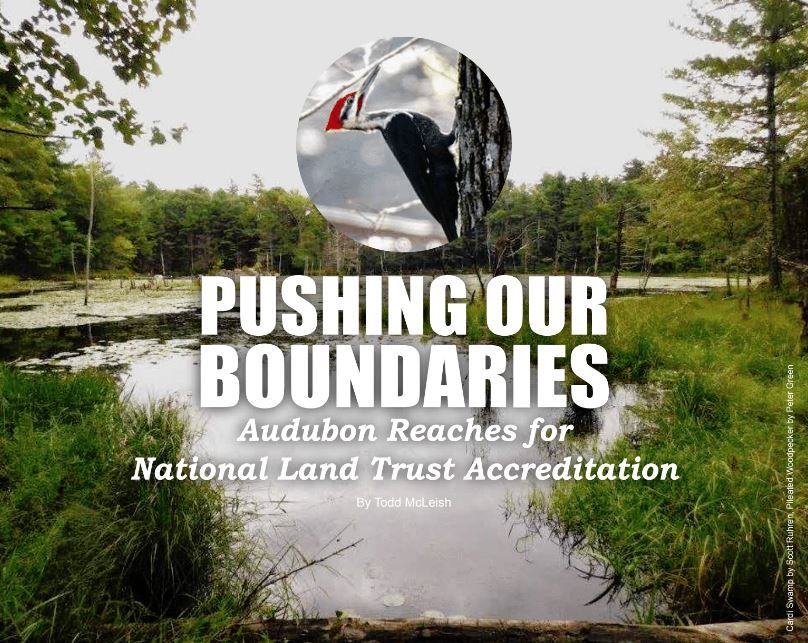

At Cardi Swamp in Foster, Scott Ruhren and Kyle Hess bushwhacked through thickets, slogged through ankle-deep mud, and traversed stone walls, small hills, and dense forests. Along the way they made note of the various habitats they encountered and recorded as many species of plants and animals as they could find on the 130-acre parcel, which was donated to Audubon in 1995.

Hess, Audubon’s conservation assistant, called it “wandering with a purpose.” He and Ruhren, the senior director of conservation, cataloged a calling Pileated Woodpecker, several green and wood frogs, an active nest of bald-faced hornets, an orange stinkhorn fungus that smelled like rotting flesh, a solitary Atlantic white cedar tree, numerous shagbark hickories, and a high-bush blueberry shrub, among many others. They also recorded several invasive species – Japanese barberry, Asiatic bittersweet and a large patch of phragmites.

The undeveloped property, which is not open to the public, showed little sign of human impacts, other than the stone wall, a distant gun shot, and the sound of cars on the nearby roadway.

The visit by Ruhren and Hess was part of Audubon’s effort to seek national land trust accreditation, an arduous process of recordkeeping, property monitoring, and policy updates that requires all Audubon lands be monitored at least once each year in the future – no matter how remote or difficult to traverse. Offered through the Land Trust Alliance, a national organization that aims to strengthen land conservation across the country, the accreditation typically takes several years to achieve. Audubon hopes to complete the process by 2020.

Audubon’s Executive Director Larry Taft said that land trust accreditation is a way of documenting and ensuring that the Society follows the proper standards and best practices in how it handles land management and conservation. The accreditation process includes a review of everything from the organization’s mission, bylaws and policies to financing, fundraising and volunteer recruitment, with a special focus on recordkeeping and monitoring of all properties acquired throughout the organization’s history.

“It’s a rigorous look under the hood at everything we do,” Taft said. “It’s all about proving how solid your organization is. And it has helped us to focus, to better understand our strengths and point out those areas where we could improve.

“The process reminds us that we have an obligation to set an example and to do really sound conservation work.” he added. “There is worry in the land protection community that careless organizations may set some bad precedents and undermine the enforceability of easements and other agreements. We want to make sure that we are safeguarding the trust that the public has placed in Audubon.”

According to Julia Sharpe, who serves on Audubon’s Council of Advisors as well as on the board of the Land Trust Alliance, more than 400 of the Alliance’s 980 member organizations have been accredited in the last decade. Five Rhode Island land trusts are already accredited – Westerly, South Kingstown, Aquidneck Island, Sakonnet and Tiverton. Nationally, those that are accredited have experienced far greater organizational growth than those that are eligible but have not yet applied. For instance, accredited land trusts have doubled their operating budgets in the last decade, compared to the 37 percent increase for non-accredited land trusts. Those that are accredited also have experienced far more significant growth in the number of private donors, staff members, volunteers and acres conserved than those that have not achieved accreditation.

“The numbers are pretty amazing,” said Sharpe. “And while the public doesn’t necessarily understand what accreditation means, it is definitely making a huge difference within the industry. Eighty-five percent of public agencies and foundations have indicated that accreditation has increased their confidence in land trusts, and now we’re beginning to see grant opportunities that are limited to accredited land trusts.”

It’s an especially challenging undertaking for an organization like Audubon, however, which is much older and has a much broader mission than traditional land trusts.

Most land trusts are less than 30 years old and own relatively few properties. Audubon, on the other hand, acquired its first parcel in 1923 and owns more land than all of the state’s land trusts put together. It is one of Rhode Island’s largest land holders, having acquired 167 properties and 25 conservation easements since its founding.

One of the biggest obstacles to accreditation for Audubon is that the documentation for many of its older acquisitions is lacking, especially for properties that are not open to the public and are seldom visited.

“We had a lot of catching up to do,” Taft said. “For many years when Audubon began acquiring properties, it was a ‘just do it’ type of organization. We went and did programs and acquired properties and then we’d figure out how to deal with any problems later. That approach used to work, but now we have a large backlog of projects that might not have the proper documentation.”

Thanks to a grant from the Rhode Island Foundation, Audubon was able to hire Hess to visit all of the properties, document the wildlife at each, and see how things have changed.

Kyle Hess at Cardi Swamp

“One good thing is that much of what is required for accreditation related to policies and finances has already come under scrutiny with our independent annual audit, so we just may need some minor tweaks,” said Taft. “But we’re still playing catch-up on site visits and management plans for our properties. That’s the fun part Kyle is doing.”

If you ask Hess, however, it’s not all fun. He started with a list of nearly 200 properties and then created a series of maps for each one.

“The challenge was dealing with older acquisitions, some with hand-drawn maps,” he said. “Just finding lot lines can be really difficult. We don’t have surveys for most properties, so I was often comparing what we have to town assessor maps, which aren’t always right and which sometimes had instructions like ‘take a left at the big oak.’”

Once he had constructed reasonably accurate perimeter maps, he visited each site to ground-truth his maps.

“I typically walk the perimeter and take pictures at every corner that I can,” Hess said. “Some boundaries might be in the middle of a river or an impassable wetland. Then I try to walk as much of the interior as possible to identify plants and animals, get an idea of what wildlife the property supports, and to monitor for human encroachment. Then I create a current condition report and a monitoring report.”

Documenting the boundaries of a seldom visited property isn’t like taking a leisurely stroll, especially for a committed conservationist like Hess.

“In my desire to document every corner of one property, I went a bit too far into a wetland and found myself up to my neck in 32-degree water,” he recalled. “My camera got ruined and I barely pulled myself out. Now I’m a lot wiser, and I’ll give in and admit that I can’t get to some spots. I just get as far as I can now.

“But I’m always finding interesting things,” Hess added, “like an old tree that was in the middle of a field that’s now completely wooded, or a house foundation somewhere you wouldn’t expect to find one. I frequently find hunters’ tree stands or trail cameras that hunters put out in hopes of documenting deer moving through.”

His field work also requires that Hess spend considerable time interacting with abutting landowners.

“Sometimes they wonder or worry about who’s out there on a property that seldom has visitors,” he said. “And sometimes those same people turn into volunteer monitors who are happy to keep an eye on the property for us.”

While Hess has spent close to three years making field visits, longtime Audubon member and volunteer Kristine Stuart has dedicated a similar amount of volunteer office time to the project. And she estimates that she still has at least a year to go.

Stuart, whose husband Everett serves on the Audubon board of directors, has the unenviable task of organizing the files for every property acquisition or easement agreement, separating the legal paperwork from the stewardship records, and ensuring that nothing vital is missing.

“Everett said that the thing that was slowing down the accreditation process was getting the property files in some sort of order,” Stuart said. “I seem to have a knack for organizing, so I said I can do that.”

Kristine Stuart has volunteered over 500 hours to organize

the files on every property that Audubon protects.

While she didn’t realize exactly what she was getting herself into, she never complains. Working alphabetically by property name, she typically selects a file and tries to figure out how best to organize the documents. It’s not uncommon for her to find 40-year-old telephone messages, jumbled wildlife survey information, and notes from discussions about an array of issues mixed in with copies of deeds, maps and wills. Many files contain multiple copies of many documents when only one is necessary.

“For Eppley, I had a full file drawer of stuff to throw out,” Stuart said. “It can be daunting.”

But she also made some interesting discoveries. While reviewing documents from the acquisition of the Lewis-Dickens Farm on Block Island, she found several hand-written letters from legendary conservationist Elizabeth Dickens to Audubon’s first executive director, Roland Clement, most of which reported on birds she had observed on the property. Those letters have now been scanned and stored electronically in Audubon’s archives.

Stuart even uncovered a ghost story from Parker Woodland in Coventry.

“For a short time, the house at Parker was rented to a man who called the office one day to report that there was a ghost on the second floor and things were flying off the walls,” she said.

Despite what most might call tedious work, Stuart is committed to continuing the project and completing it in time for the accreditation review.

“Most of my career I did a lot of long-term projects, and you know that they’re going to take a while,” she said. “I actually enjoy the work. I enjoy the chatter of conversations in the office, and I enjoy finding these little personal stories. And for a short time, I get to know each of the properties.”

Ruhren is especially appreciative of the work she has done.

“Kristine has been terrific at sorting through all the records, putting them in order, and purging what she can. It’s been a huge commitment to get things in order, but in the end, it’s going to be a benefit to our conservation efforts to have this accreditation. It builds Audubon’s reputation and it adds cachet to grant applications.”

Taft agrees. “It may sound like it’s just a lot of housecleaning, and it is, but at the same time, when something comes up related to some of our properties, we know we’ll have the answer,” he said. “I’m thrilled we’ve come this far and all this work is well worth the end result of national accreditation.”

• • •

Todd McLeish is a life-long birder, freelance science writer and author of several books about wildlife, including “Return of the Sea Otter.”